Autumn camping

This weekend I was lucky enough to get well out of the city and into some optimal fall weather. There was even some canoeing.

For Thanksgiving weekend, I am planning to do a camping trip with some friends where we will also do some campsite and trail repairs.

September rain

Today was unusually draining.

I rode in through the rain, skipping breakfast to give myself more time to sleep / cycle a little slower; then didn’t feel the allure of BBQ food so skipped lunch; then got caught up in a too-long task which became overly too long because of the hunger and tiredness.

I also keep seeing event notifications for ghost rides for newly slain cyclists — sometimes with the galling euphemism/evasion “bicycle accident”, when crashes involving just bicycles are seldom fatal and what is generally being left unsaid for politeness in these notices is “killed by a car”.

Still, I rode home safely, made a nice meal, and am progressing toward feeling capable of handling life’s affronts.

“Explore Worlds”

Milan Ilnyckyj Policy on Sincere Invitations

Please believe that this post is not prompted by any recent incident, but rather by something I have long observed and recently had some clarifying conversations about.

I have always been vexed and perplexed by insincere invitations of all kinds, when done out of politeness or as a kind of social reflex: “You must come to the house for lunch sometime…”

I do not like not knowing if a sincere offer is being made, and I do not like following up to have the offering party just awkwardly never get to the point of saying that an invitation had not been sincere.

For the benefit of my friends, colleagues, and relations, I will briefly and simply enunciate my own policy so that you may understand what an invitation from me means:

My invitations are sincere.

Specifically, they are not insincere in that I am not actually proposing to do the thing suggested. If I suggest having lunch sometime, I do really mean to break out calendars and arrange and execute such a plan. If you say yes and the fates allow, there will be lunch.

They are also not insincere in the sense of being a coded signal for something else. I am curious about a limitless number of things, so if I suggest we take a walk sometime and have a detailed discussion on some subject, or take a bike ride around the city, or whatever – I do actually, literally, specifically mean we should do those things.

Thank you for your attention.

Toronto is a bike city

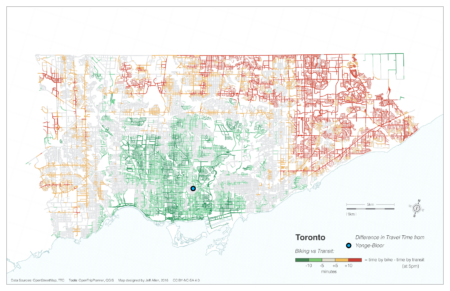

A friend from the Toronto group bike ride community directed me to Jeff Allen’s intringuing and beautiful cartographic work.

One especially striking map – which supports my view that bicycling has become the best and fastest form of transport in Toronto – shows which areas it is faster to reach from Yonge-Bloor by bike than by transit during rush hour:

You can get a long way! Straight north to York Mills. Southwest past the mouth of the Humber. Southeast past Tommy Thomson Park and into Scarborough.

The map is from 2016, but I would imagine things are worse now with transit underfunding and all the slowdown zones, plus all the streets blocked up by summer construction.

A year since moving in

Conformity versus competence

[I]n most hierarchies, super-competence is more objectionable than incompetence.

Ordinary incompetence, as we have seen, is no cause for dismissal: it is simply a bar to promotion. Super-competence often leads to dismissal, because it disrupts the hierarchy, and thereby violates the first commandment of hierarchal life: the hierarchy must be preserved.

…

Employees in the two extreme classes—the super-competent and the super-incompetent—are alike subject to dismissal. They are usually fired soon after being hired, for the same reason: that they tend to disrupt the hierarchy.

Peter, Laurence J. and Hull, Raymond. The Peter Principle. Buccaneer Books, 1969. p. 45-6

Related: Whose agenda are you devoted to?

Neon Riding through campus

Photo by Ed Ng

“The Rest is History” podcast

A recent Economist article drew my attention to the “The Rest is History” podcast. I enjoyed multi-part series’ about Lord Byron and Martin Luther, as well as a one-parter about the Hapsburg monarchy.

With an eye to researching my long-term Sherlock Holmes / Isambard Kingdom Brunel pastiche, I am listening to their series on the Titanic. The first episode provides a bit of imagery that helps with understanding shipyards of the era and how they were perceived:

I saw churches of all dominations. Freemason, Orange lodges, wide streets, towering smokestacks, huge factories, crowded traffic. And out of the water, beyond the custom house, dimly seen through smoke and mist rose some huge shapeless thing which I found to be a shipbuilding yard where in 10,000 men were hammering iron and steel into great ocean liners… The noise of wheels and hoofs and cranks and spindles and steam hammers filled my ears and made my head ache.

The transcript leaves me a bit confused about the source of the quote. I think the transcript attributes it to Richard Davenport-Hines, but a full text search seems to place it in William Bulfin’s “Rambles in Eirinn.”

One of the main reasons it’s fun to have low-pressure writing projects like my Holmes pastiche and the STS-27/107 screenplay is that it both gives license and provides purpose for reading around the topic. “The Rest is History” is a nice resource for improving contextual understanding, and it’s a whole lot more pleasant to listen to during a bike ride than the news is.