We have arrived safe in North Vancouver via Kamloops, Lillooet, and Whistler — managing to avoid any major fire delays more by luck and Sasha’s dedication behind the wheel than by foresight and planning. He did all our driving in three back to back days, and did today’s stretch through the heaviest traffic, steepest and twistiest roads, and our only night driving of the voyage.

We worked in a few short pauses to enjoy the views from the mountains. I hadn’t realized how beautiful the area around Lillooet is, with a semi-arid landscape, rocky peaks overhead, and vertiginous drops into the river canyon. It would be a fine place to return in no hurry and with a tripod and landscape photography gear. A hot tip from a German man at a roadside viewpoint took us on a ten minute hike to a stunning panoramic view at 50.65983, -121.98589.

A stop in Pemberton yielded kimchi and pulled pork sandwiches and smashed fries, which seemed just right as our last rest and meal of the journey.

After a night in tents and three solid days of driving, the last stretch in the dark through Whistler and Squamish had Sasha showing his only noticeable fatigue of the journey, which we countered with lively songs and an effort I made to dance in my seat to kinetically counteract the idea of tiredness.

Our parents welcomed us late in the evening with great hospitality and kindness. Because of the fires and the importance of Sasha not driving when too tired, I had been planning based on a five day drive with two extra days for delays and detours. As a result, I am in Vancouver with five days before the next phase of this visit is to begin. To pack light, I omitted to bring any camera gear, so my hope of digitizing the family albums on this visit is set aside.

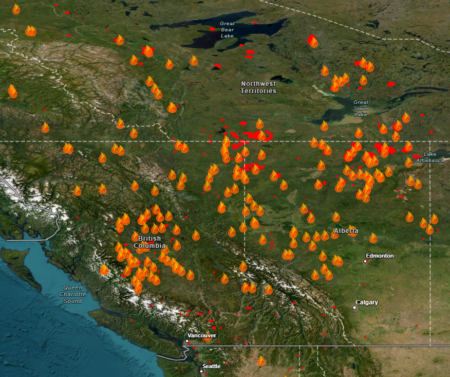

While the time together was joyful and rewarding, we did spend the day very concerned about the fire threatening Bechoko. I watched the news and fire map updates while Sasha kept up with friends over messages and social media. The danger there is great and everyone has been directed to evacuate, and the structures and environs of the community are in peril. All we can do now is hope that the three homes that have already been lost will be all that are taken, and then regardless of the actual damage realized during this fire season do what we can to support the people impacted. I wish this unprecedented fire season was having a decisive political effect, pushing the public and politicians to accept that it is madness and a profound and irreversible betrayal of the young to keep producing and expanding fossil fuels. It isn’t really prosperity when you get or stay rich by burning up the prospects of those who will come after you, but our cognitive blockages to accepting and taking responsibility for the consequences of our actions continue to paralyze us into accepting a world-wrecking status quo. I don’t know what can break that complacency, but the way in which we carry on heedlessly incinerating the future with our coal, oil, and gas dependence is setting us up to be justly remembered as the generations that squandered the common heritage of humankind for the sake of our own ease and enjoyment.