During the last couple of months, I have been involved with establishing a local chapter of the climate change organization 350.org. Since the organization has no money, it relies upon the work of volunteers during their spare time. This is good in many ways, since it means the group consists of people who have a personal conviction that it is necessary to take action on climate change and that they are willing to devote their talents to the project.

All told, the process of organizing differs substantially from the kind of analysis that happens in government and academia. Indeed, I wonder how much the skills required for good organizing and good analysis overlap. The key requirement for organizing seems to be an ability to motivate people to take action. For that action to be effective, it is obviously necessary to have a big-picture understanding about the science and politics of climate change. At the same time, an active awareness of the scale of the problem may hamper effective organizing. It is impossible to honestly claim that any single action or campaign will make a major difference in the trajectory of Canada’s emissions, much less those of the world as a whole. Motivation requires the hope that one person’s actions will make a difference; analysis often suggests that the actions will have no perceptible effect.

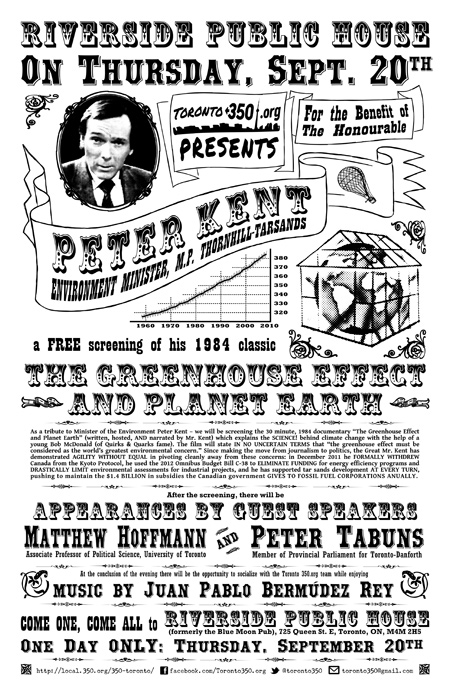

Climate change is a problem without precedent. That means we cannot know in advance which strategies could succeed in curbing it. Given how threatening and urgent it is, I think we need to try everything simultaneously: technological development, political lobbying, grassroots organizing, and all the rest. If nothing else, organizing 350.org is a way of getting in touch with people who are serious about the problem. Together, we can do a better job of evaluating our efforts, spotting opportunities, and correcting mistakes.

P.S. If you are in Toronto and interested in helping to prevent dangerous climate change, I would appreciate if you would join the 350 Toronto mailing list. If you really want to make a difference, please get in touch with me about joining our organizing team.