Revising the fish paper, and reading Bromley and Paavola on environmental economics, the question of the nature of ethical resource relations between the rich and poor world keeps arising. In particular, the issue of paternalism is persistent. The question must be asked of whether there are individuals or groups who ‘know better’ when it comes to environmental choices and, if so, how the superiority of their understanding can be verified and legitimated.

Whether it is Angolan diamonds or West African fish, there is often a case to be made that rich world access to commodities in the poor world has harmful effects. It may fuel conflicts (as with diamonds), it may reduce the future possibilities for resource use within the poor countries (as with fish), and it may enrich corrupt or non-representative elites while not benefitting the population at large. People have generally been critical of the Chinese government for striking resource deals with states that the west shuns because of their poor human rights records and lack of democratic credentials.

The big question, it seems, is how to treat the interests of people in non-representative political systems. Do people in democratic systems (or rich countries) have an obligation to effectively act as their agents, anticipate their preferences, and try to guide outcomes towards satisfying them?

Much recent policy seeks to do exactly this. When China decides that the electricity and prestige generated by the Three Gorges Dam is worth more than the flooded territory and other costs of construction, on what basis can or should we say that they are wrong? We can accuse them of short-term thinking (though our right to do so in anything beyond an advisory manner is dubious) or of violating the rights of individuals (which almost always happens when people are forced to do things in systems that lack political and legal accountability). All that said, the idea that rich states or international organizations can take up the cause of representing the general population of China strikes me as a problematic one.

Naturally, there are also accusations of hypocrisy. How many environmental choices within the rich world have been made on the basis of short-term thinking? How many have harmed a great many individuals for dubious value? Do not the states which are undergoing the process of development today have the right to make the same mistakes as states that have already developed did in the past? To the last of those, it can be responded that our level of understanding about the world has improved substantially since the industrial revolution. When developed states first used DDT, they were not aware of important consequences the introduction of that chemical into the environment would have. Arguably, the same can be said of all the coal that was burned to generate steam power and electricity. The trickier question is whether improved knowledge creates an obligation on the part of developing states to make choices that avoid incurring the kind of harms already suffered in the developed world.

There are also international efforts to encourage better environmental policy that might reasonably be seen as empowering, rather than paternalistic. The Publish What You Pay Initiative and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative are trying to encourage (or require) resource extracting firms to publish the details of their contracts with governments. This allows scrutiny by the domestic regulators of the firms, by different branches of the governments involved in the contracts, by people living under the authority of those governments, and by international bodies. Presumably, having access to such information could allow for the mobilization of political energy, on the part of any or all of those organizations. At first glance, this model is more appealing than the paternalistic one.

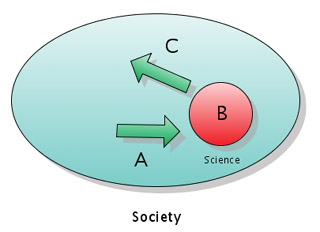

In the end, this is reflective of a larger overall tension within environmental debates. There are certain groups that are often willing to promote optimum outcomes (scientists and economists in particular) that are based on analyses that are rigorous according to standards established within their own disciplines. Then, there is a political process that arrives at decisions on the basis of ongoing political realities – many of which have nothing to do directly with the nature and importance of the environmental issues in question. Finally, there are those who assert the fundamental rightness of views or policies on the basis of some combination of these considerations and others. Such a view suggests that there is an ideal policy (or at least a better policy) out there, but that its nature is not fully captured in technocratic assessment and does not arise spontaneously from the political process. I believe this intuitively, but have a great deal of trouble sketching out the details.

On what basis, however, can the desirability of this kind of policy be asserted? One mechanism is democratic endorsement. Many theorists assert the value of open discussion as a mechanism through which policy might be chosen. Of course, translating discussion into action brings it up against all the barriers produced by existing distributions of power. Likewise, people are not equally capable of engaging in discussion – especially when expert knowledge is a required currency in order for arguments to be taken seriously.

These are not questions to which I see straightforward answers. There is no group that can be trusted to evaluate the situation from a neutral perspective. There is likewise no solid way to assert which values are important, and how important each is with respect to others. The easiest solution, from the perspective of those trying to act in the world, is to identify those areas where present practice deviates most substantially from ideal practice as best understood, and where the gap between the two can be closed or reduced through available and acceptable means. I call this the strategy of picking low-hanging fruit. Of course, the assumption behind this strategy is that the big questions above will eventually be resolved to the satisfaction of most, allowing for further progress. There is plenty of reason to be skeptical about that.