Category: Space and flight

Posts about flying in atmospheres, or outside of them

Lego Space Shuttle Discovery deploying Hubble Space Telescope

Lego Women of NASA

Nancy Grace Roman with the Hubble Space Telescope; Mae Jemison and Sally Ride with the Space Shuttle; and Margaret Hamilton with listings of the software she and her MIT team wrote for the Apollo Program

Waiting for my Lego shuttle

In part because of housing uncertainty — and mindful of George Monbiot’s excellent advice about true freedom arising from low living expenses “If you can live on five thousand pounds a year, you are six times as secure as someone who needs thirty thousand to get by” — I have been avoiding and minimizing taking on new physical possessions.

Nonetheless, with my interest in space and the Space Shuttle program specifically, I could not resist ordering Lego’s new Space Shuttle Discovery and Hubble Space Telescope set on the day of its release.

The Hubble is arguably the greatest scientific achievement of the Space Shuttle program and certainly one of the most powerful instruments humanity has ever created for understanding the vastness and history of our universe. The dimensions of the Hubble also did a lot to dictate the final size and configuration of the shuttle (less for the telescope itself, and more for the secret Earth-observing versions operated by the National Reconnaissance Office). Those design decisions, in turn, did much to shape the shuttle’s operational characteristics and history, including the design choices that contributed to the Challenger and Columbia losses.

The set will be fun to put together, and I should be able to find somewhere to display it even if I end up living in a tiny space.

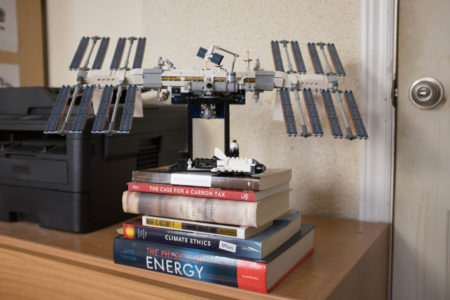

Lego ISS

Starlink in the Canadian north

SpaceX’s Starlink satellite constellation promises to provide low-latency high-bandwidth internet to anyone on the planet.

In November or so, the company announced a beta release in Canada. Some northern communities are already being connected, notably Pikangikum in northwestern Ontario with the charitable assistance of FSET Information Technology and Service.

With my brother Mica starting to teach at the Chief Jimmy Bruneau School in Behchoko, about 125 km down the highway from Yellowknife, we both wondered whether the satellite internet package might be useful for them.

So far, I have found three explanations for why Starlink isn’t available in the region yet:

- SpaceX doesn’t yet have the necessary satellites to support access from that latitude

- SpaceX needs ground stations in areas where there will be customers

- Starlink needs to negotiate with Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) for use of the Ka radio band

I have reached out to bureaucrats and people in ministers’ offices to try to get authoritative information on what the issue is.

This post — based around this map — shows a station in Kaparuk, Alaska. I sent a message to the map’s creator for verification, since I can’t see how satellites going from pole to pole could cover Alaska but not the Canadian territories. This post shows a Starlink ground station in St. John’s Newfoundland.

If you have any relevant information please contact me. If you are also looking into getting a Starlink connection in northern Canada I don’t have any further information for now but I will provide updates when I do.

SpaceX and US crewed launch capability

Since STS-135 in 2011 and the retirement of the Space Shuttle, the only way for human beings to reach orbit has been a Soyuz launch from Baikonur. On May 27th, SpaceX is scheduled to launch the first crew from the US in nine years.

There are good reasons to be skeptical about human spaceflight (especially by useless space tourists, or ballastronauts), but there is something useful and unifying about the International Space Station as a science platform and humanity’s only effort at a permanent human settlement off the Earth.

Gravitational waves and multi-messenger astronomy

Most of the history of astronomy consists of observing electromagnetic radiation from outside our planet. That includes the light which shines off the sun and reflects from bodies in the solar system, as well as radio waves produced by phenomena around the universe including pulsars.

Now that we also have neutrino detectors and gravitational wave detectors like LIGO we can receive signals of other kinds from around the universe, helping us to understand it all better. One neat trick: since the universe did not allow the transmission of light for the first 400,000 years there is a limit to how far back we can look by electromagnetic means.

You can sign up for neutrino burst warnings, in case they indicate something great happening in the sky that you may wish to observe by other means.

Nominal ride to orbit

A solar sail is functional in space

It’s possible to perform orbital maneuvers which would normally require fuel using instead the momentum of sunlight.

Via the incomparable Scott Manley: Lightsail 2 Sails On Sunlight At Last