As he headed upstairs for lunch in the private dining room at Massey College today, I was able to hand a short letter about climate change to Prime Minister Stephen Harper. He accepted it very graciously and suggested we pose for a photo. I also gave a copy of the letter to Master Fraser, who was accompanying him.

Category: Science

New discoveries, the scientific method, and all matters relating to the scientific study of the physical world

The hostile media effect and imagination of audience

Recent work by Gunther and Schmitt (2004) on the hostile media effect offers a partial clarification of our findings. These authors conducted an experiment in which a purposefully crafted neutral text was presented to experts involved in the ongoing controversy over genetically modified organisms. For one randomized group of experts, this text was presented as a news item; for the other, the identical text was presented as a research paper from a senior undergraduate student. In comparing participants’ evaluations of bias in the text, Gunther and Schmitt found striking differences. Whereas the presentation of the text as a news item yielded extreme and contradictory assessments of bias, the identical text presented as an undergraduate research paper was generally judged to be balanced. The authors argue that this reflects the importance of experts’ “imagination of audience” as a critical factor in their understanding of texts and communications. In this sense, experts are reacting against the media based on their understanding of the competency and vulnerability of the general public: “Partisans may believe that information in a mass medium will reach a large audience of neutral, and perhaps more vulnerable, readers – readers who could be convinced by unbalanced or misleading information to support the ‘wrong’ side.” In short, Gunther and Schmitt’s research suggests that negative views of the media related more directly to experts’ views of the general public than to the behaviours of media institutions themselves.

Young, Nathan and Ralph Matthews. The Aquaculture Controversy in Canada: Activism, Policy, and Contested Science. 2010. p. 149 (paperback)

Force of Nature: The David Suzuki Movie

Yesterday, I was part of a panel discussion and film screening at Hart House. They showed Force of Nature: The David Suzuki Movie, which I found to be ambitious and engaging. It combines footage from Suzuki’s 75th birthday lecture with a biography of his life, including his family’s internment by the British Columbia authorities during world war two, his work at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, his biological research at the University of British Columbia, as well as his activism and personal life.

The film involved a great deal of travel and one-on-one time with Suzuki, as they visited most of the important places in his life. It was also skilfully mixed with archival footage, though a bit of it may have been misleading (notably, the cut from the Hiroshima atomic explosion to footage of the totally unrelated Castle Bravo thermonuclear test, and the footage of the K-25 gaseous diffusion plant at Oak Ridge, which had nothing to do with Suzuki’s biological research at Oak Ridge).

All told, I definitely recommend seeing the film if you get the chance. It says very little about precisely what should be done to address the world’s environmental problems, but rather a great deal about why we ought to be making the effort.

Canada not on track to meet its (inadequate) climate targets

In the news today:

Canada won’t come close to meeting emissions target: Environment Canada

…

The latest internal government report confirms Canada is not close to being on track to meet its promised target for emissions cuts by the year 2020.

In fact, the Environment Canada analysis released Thursday indicates the country slipped backward in 2012 in terms of achieving the government’s greenhouse gas emissions target under the Copenhagen Accord.

Under that international agreement, Prime Minister Stephen Harper committed in 2009 to cutting Canada’s emissions 17 per cent from 2005 levels by the year 2020.

…

Even with long-overdue government regulations on the oil and gas sector, which have not yet been announced, Environment Canada doesn’t foresee a scenario where the 2020 target will be met.

Previously: Can Canada meet the Conservative GHG targets?

The Varsity on fossil fuel divestment

In todays’ edition of The Varsity, there is an interview about the Toronto350.org divestment campaign at the University of Toronto.

In addition to quoting me and the Office of the President, it quotes Justin Lee, president of U of T’s Rational Capital Investment Fund, claiming that we are needlessly politicizing the issue of investment and implying that divestment would be bad for the portfolio. I wish he had read section 4 of the brief, in which we explain why divestment is a smart idea financially. These investments are not compatible with long-term prosperity for the world, since the business plans of these companies are focused on activities that would guarantee dangerous climate change. They are also incompatible with the long-term prosperity of the university itself, since the assumption that these companies will be able to burn all the fuel they own will eventually be invalidated.

Also, the fact that the university has a divestment policy in the first place shows that they understand how their investment choices do have ethical implications which are rightly a concern of the school. This isn’t a matter of needlessly politicizing university investment – it’s about bringing U of T’s investment policy in line with its values and long-term financial interest.

Ignaz Semmelweis

Most people have probably heard how the first person who suggested that doctors wash their hands before delivering babies in order to prevent infections was ridiculed and rejected. I didn’t realize quite how far his persecution went:

After he published his findings, though, many of his colleagues were offended at the suggestion that they did not have clean hands. After all, doctors were gentlemen and as Charles Meigs, another obstetrician, put it, “a gentleman’s hands are clean”. Discouraged, Semmelweis slipped into depression and was eventually committed to a lunatic asylum. He died 14 days later, after being brutally beaten by the guards.

Perhaps the lesson to be drawn is: don’t underestimate how willing self-policing groups of experts can be to reject important new information in order to protect their self-image and prestige.

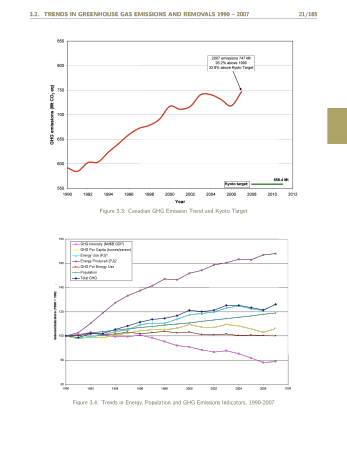

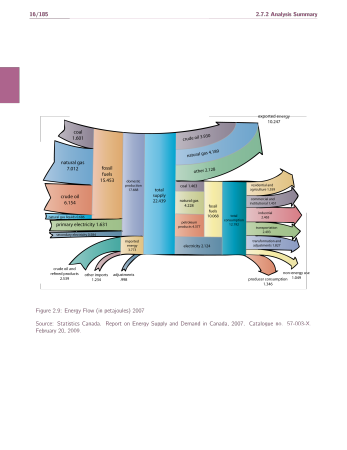

Canada’s greenhouse gas trends and breakdown

Interesting material:

For one thing, it shows what a huge quantity of GHG pollution Canada exports in the form of fossil fuels.

From Canada’s Fifth National Communication on Climate Change. 2010. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/natc/can_nc5.pdf

From MaddAddam

The people in the chaos cannot learn. They cannot understand what they are doing to the sea and the sky and the plants and the animals. They cannot understand that they are killing them, and that they will end by killing themselves. And there are so many of them, and each one of them is doing part of the killing, whether they know it or not. And when you tell them to stop, they don’t hear you.

So there is only one thing left to do. Either most of them must be cleared away while there is still an earth, with trees and flowers and birds and fish and so on, or all must die when there are none of those things left. Because if there are none of those things left, then there will be nothing at all. Not even any people.

So shouldn’t you give those ones a second chance? he asked himself. No, he answered, because they have had a second chance. They have had many second chances. Now is the time.

Atwood, Margaret. MaddAddam. 2013. p. 291 (hardcover)

Brief done

I have finished with the substantive work on the Toronto350.org fossil fuel divestment brief. It is now open for endorsement by members of the University of Toronto community, including teaching staff, students, administrative staff, and alumni.

The Economist on China and climate change

Some important and sobering information from a recent article:

China’s impact on the climate, though, is unique. Its economy is not only large but also resource-hungry.

…

The country’s energy use is… gargantuan. This is in part because, under Mao, the use of energy was recklessly profligate. China’s consumption of energy per unit of GDP tripled in 1950-78—an unprecedented “achievement”. In the early 1990s, at the start of its period of greatest growth, China was still using 800 tonnes of coal equivalent (tce, a unit of energy) to produce $1m of output, far more than other developing countries. Energy efficiency has since improved; China used 390tce per $1m in 2009. But that was still more than the global average of 300tce and far more than Germany, which used only 173tce.

Despite a huge hydroelectric programme, most of this energy comes from burning coal on a vast scale. China currently burns about half the world’s supplies. In 2006 it surpassed America in carbon-dioxide emissions from energy. By 2014 or 2015 it will emit twice America’s total. Between 1990 and 2050 its cumulative emissions from energy will amount to some 500 billion tonnes—roughly the same as those of the whole world from the beginning of the industrial revolution to 1970. And the total is what matters. The climate reacts to the stock of carbon, not to annual rises.

These emissions are adding to a build-up of carbon already pushed to unprecedented heights by earlier industrialisations. When Britain began the process in the 18th century, the atmosphere’s carbon-dioxide level was 280 parts per million (ppm). When Japan was industrialising fastest in the late 1950s, it had risen a bit, to 315ppm. This year the level hit 400ppm. Avoiding dangerous climate change is widely taken to mean keeping below 450ppm, although there are significant uncertainties surrounding this figure. At current rates that threshold will be reached in 2037. China is likely to be the largest emitter between now and then.

About a quarter of China’s carbon emissions is produced making goods for export. If the carbon embodied in those goods were marked against the ledgers of the importing countries China would look a little less damaging, the rich world a lot less virtuous. But even allowing for that, China is not playing catch-up any more. It is doing more damage to the stability of the global climate than any other country.

The claim that stabilizing the atmospheric concentration at 450 ppm will be enough to keep temperature increases below 2˚C is dubious. In James Hansen et al. “Target Atmospheric CO2: Where Should Humanity Aim?“, they conclude that: “If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm”.

Doing that would require much more aggressive action than what this article suggests.