Talking with Dr. Hurrell about the thesis this evening was rather illuminating. By grappling with the longer set of comments made on my research design essay, we were able to isolate a number of interwoven questions, within the territory staked out for the project. All relate to science and global environmental policy-making, but they approach the topic from different directions and would involve different specific approaches and styles and standards of proof.

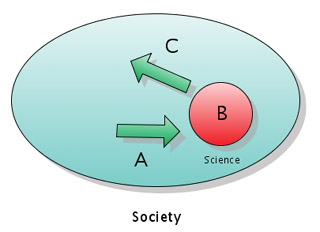

The first set deal with the role of ‘science’ as a collection of practices and ideals. If you imagine society as a big oval, science is a little circle embedded inside it. Society as a whole has a certain understanding of science (A). That might include aspects like objectivity, or engaging in certain kinds of behaviour. These understandings establish some of what science and scientists are able to do. Within the discipline itself, there is discussion about the nature of science (B), what makes particular scientific work good or bad, etc. This establishes the bounds of science, as seen from the inside, and establishes standards of practice and rules of inclusion and exclusion. Then, there is the understanding of society by scientists (C). That understanding exists at the same time as awareness about the nature of the material world, but also includes an understanding of politics, economics, and power in general. The outward-looking scientific perspective involves questions like if and how scientists should engage in advocacy, what kind of information they choose to present to society,

The next set of relationships exist between scientists and policy-makers. From the perspective of policy-makers, scientists can:

- Raise new issues

- Provide information on little-known issues

- Develop comprehensive understandings about things in the world

- Evaluate the impact policies will have

- Provide support for particular decisions

- Act in a way that challenges decisions

For a policy-maker, a scientist can be empowering in a number of ways. They can provide paths into and through tricky stretches of expert knowledge. They can offer predictions with various degrees of certainty, ranging from (say) “if you put this block of sodium in your pool, you will get a dramatic explosion” to “if we cut down X hectares of rainforest, Y amount of carbon dioxide will be introduced into the atmosphere.”

The big question, then, is which of these dynamics to study. Again and again, I find the matter of how scientists understand their legitimate policy role to be among the most interesting. This becomes especially true in areas of high uncertainty. The link from “I know what will happen if that buffoon jumps into the pool strapped to that block of sodium” to trying to stop the action is more clear than the one between understanding the atmospheric effects of deforestation and lobbying to curb the latter. Using Stockholm as a ‘strong case’ and Kyoto as a ‘weak case’ of science leading to policy, the general idea would be to examine how scientists engaged with both policy processes, how they saw their role, and what standards of legitimacy they held it to. This approach focuses very much on the scientists, but nonetheless has political saliency. Whether it could be a valid research project is a slightly different matter.

The first big question, then, is whether to go policy-maker centric or scientist centric. I suspect my work would be more distinctive if I took the latter route. I suspect part of the reason why the examiners didn’t like my RDE was because they expected it to take the former route, then were confronted with a bunch of seemingly irrelevant information pertaining to the latter.

I will have a better idea about all of this once I have read another half-dozen books: particularly Haas on epistemic communities. Above all, I can sense from the energy of my discussions with Dr. Hurrell that there are important questions lurking in this terrain, and that it will be possible to tackle a few of them in an interesting and original way.

Watching this video about the Large Hadron Collider (a particle accelerator under construction at CERN), I was reminded of something I was wondering about a few weeks ago. People talk about the universe being the size of a grain of sand, or the size of a marble, in the moments immediately following the big bang. That seems comprehensible enough, but there is a fundamental problem with the analogy. The marble sized thing isn’t just all the mass in the universe, expanding into space that existed prior to the ‘explosion.’ Instead, space and time were supposedly unfurling simultaneously.

Watching this video about the Large Hadron Collider (a particle accelerator under construction at CERN), I was reminded of something I was wondering about a few weeks ago. People talk about the universe being the size of a grain of sand, or the size of a marble, in the moments immediately following the big bang. That seems comprehensible enough, but there is a fundamental problem with the analogy. The marble sized thing isn’t just all the mass in the universe, expanding into space that existed prior to the ‘explosion.’ Instead, space and time were supposedly unfurling simultaneously.

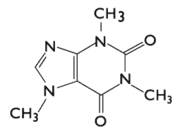

Caffeine – a molecule I first discovered as an important and psychoactive component of Coca Cola – is a drug with which I’ve had a great deal of experience over the last twelve years or so. By 7th grade, the last year of elementary school, I had already started to enjoy mochas and chocolate covered coffee beans. When I was in 12th grade, the last year of high school, I began consuming large amounts of Earl Gray tea, in aid of paper writing and exam prep. During my first year at UBC, I started drinking coffee. At first, it was a matter of alternating between coffee itself and something sweet and delicious, like Ponderosa Cake. By my fourth year, I was drinking more than 1L a day of black coffee: passing from French press to mug to bloodstream in accompaniment to the reading of The Economist.

Caffeine – a molecule I first discovered as an important and psychoactive component of Coca Cola – is a drug with which I’ve had a great deal of experience over the last twelve years or so. By 7th grade, the last year of elementary school, I had already started to enjoy mochas and chocolate covered coffee beans. When I was in 12th grade, the last year of high school, I began consuming large amounts of Earl Gray tea, in aid of paper writing and exam prep. During my first year at UBC, I started drinking coffee. At first, it was a matter of alternating between coffee itself and something sweet and delicious, like Ponderosa Cake. By my fourth year, I was drinking more than 1L a day of black coffee: passing from French press to mug to bloodstream in accompaniment to the reading of The Economist.