I had an idea several years ago that I think is worth writing up. It is for a system to lift any kind of cargo from a low orbit around a planet into a higher one, with no expenditure of fuel.

Design

The system consists of two carriers: one shaped like a cylinder with a hole bored through it and the other shaped like a cigar. The cigar must be able to pass straight through the hole in the cylinder. The two must have the same mass, after being loaded with whatever cargo is to be carried. This could be achieved by making the cylinder fairly thin, by making the cigar longer than the cylinder, or by having the latter denser than the former. Within the cavity of the cylinder are a series of electromagnets. Likewise, under the skin of the cigar. Around the cylinder is an array of photovoltaic panels. Likewise, on the skin of the cigar. Each contains a system for storing electrical energy.

In addition to these main systems, each unit would require celestial navigation capability: the ability to determine its position in space using the observation of the starfield around it, as modern nuclear warheads do. This would allow it to act independently of ground-based tracking or the use of navigation satellites. It would also require small thrusters with fuel to be used for minor orbital course corrections.

Function

The two objects start off in low circular or elliptical orbits, along the same trajectory but in opposite directions. Imagine the cylinder transcribing a path due north from the equator to the north pole and onwards around the planet, while the cigar transcribes the same path except in the opposite direction: heading southwards after it crosses the north pole. The two objects will thus intersect each time they complete a half-orbit.

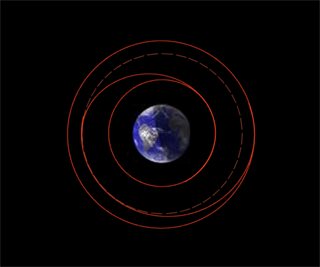

As each vehicle circles the planet, it gathers electrical power from solar radiation using the attached photovoltaic panels. When the two orbits intersect, the electromagnets in the cigar and the cylinder are used so as to repel one another and increase the velocity of each projective, in opposite directions, by taking advantage of Newton’s third law of motion. Think of it being like a magnetically levitated train with a bit of track that gets pushed in the opposite direction, flies around the planet, and meets up with the train again. I warn you not to mock not the diagram of the craft! Graphic design is not my area of expertise. Obviously, it is not to scale.

The orbits

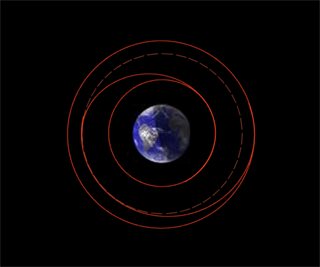

The diagram above demonstrates the path that one of the craft would take (see the second update below for more explanation). The dotted circle indicates where the two craft will meet for the first time, following the initial impulse. At that point, you could either project up to a higher elliptical orbit or circularize the orbit at that point. This process can be repeated over and over. Here is a version showing both craft, one in red and the other in brown. See also, this diagram of the Hohmann transfer orbit for the sake of comparison. The Hohmann transfer orbit is a method of raising a payload into a higher orbit using conventional thrusters.

The basic principle according to which these higher orbits are being achieved is akin to one being a bullet and the other being the gun. Because they have equal mass, the recoil would cause the same acceleration on the gun as it did on the bullet; they would start moving apart at equal velocity, in opposite directions. Because they can pass through one another, the ‘gun’ can be fired over and over. Because the power to do so comes from the sun, this can happen theoretically take place an infinite number of times, with a higher orbit generated after each.

Because each orbit is longer, the craft would intersect less and less frequently. This would be partially offset by the opportunity to collect more energy over the course of each orbit, for use during the boosting phase.

As such, orbit by orbit, the pair could climb farther and farther out of any gravity well in which it found itself: whether that of a planet, asteroid, or a star. Because the electromagnets could also be used in reverse, to slow the two projectiles equally, it could also ‘climb down’ into a lower orbit.

Applications

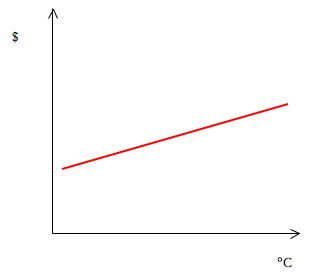

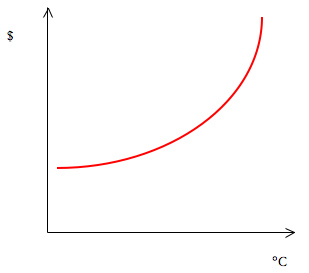

On planets like Earth, with thick atmospheres, such a system could only be used to lift payloads from low orbits achieved by other means to higher orbits. The benefit of that could be non-trivial, given that a low orbit takes place at about 700km and a geostationary orbit as used for communication and navigation satellites is at 35,790 km. Raising any mass to such an altitude requires formidable energy, despite the extent to which Earth’s gravity well becomes (exponentially) less powerful as the distance from the observer to the planet increases.

A system of such carriers could be used to shift materials from low to high orbit. The application here is especially exciting in airless or relatively airless environments. Ores mined from somewhere like the moon or an asteroid could be elevated in this way from a low starting point; with no atmosphere to get in the way, an orbit could be maintained at quite a low altitude above the surface.

Given a very long time period, such a device could even climb up through the gravity well that surrounds a star.

Problems

The first problem is one of accuracy. Making sure the two components would intersect with each orbit could be challenging. The magnets would have to be quite precisely aligned, and any small errors would need to be fixed so the craft would intersect properly. Because of sheer momentum, it would be an easier task with more massive craft. More massive vehicles would also take longer to rise in the gravity well through successive orbits, but would still require no fuel do so, beyond a minimal amount for correctional thrusters, which could be part of the payload.

Another problem could be that of time. I have done no calculations on how long it would take for such a device to climb from a low orbit to a high one. For raw ores, that might not matter very much. For satellite launches, it might matter rather more.

Can anyone see other problems?

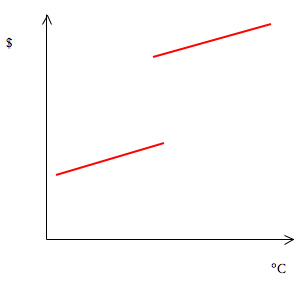

[Update: 7:26pm] Based on my extremely limited knowledge of astrophysics, it seems possible the successive orbits might look like this. Is that correct? My friend Mark theorizes that it would look like this.

[Update: 11 August 2006] Many thanks to Mark Cummins for creating the orbital diagram I have added above. We are pretty confident that this one is correct. He describes it thus: “your first impulse sends you from the first circle into an elliptical orbit. When your two modules next meet, (half way round the ellipse), you can circularize your orbit and insert into the dotted circle, or you can keep “climbing”, an insert into a larger ellipse. Repeat ad infinitum until you are at the desired altitude, then circularize.”