A book of magic tricks that I owned in elementary school included a number of ‘tricks’ that worked because of the properties of the Mobius Strip. I realize now what an insult they were to geometry. Yes, it may seem amazing that you can draw a line all the way around or cut a Mobius strip along its centre and have it turn into a larger loop, but to attribute these things to ‘magic’ is absurdly anti-educational. You might as talk about how the angles in a triangle ‘magically’ add up to 180 degrees.

Category: Rants

Posts where I spout off on one topic or another

Electronic botherations

I obviously haven’t been making frequent enough offerings to whichever god watches over electronic devices. First, my digital camera got some kind of dust or mold permanently inside. Since it’s not a camera with lenses that can be switched, there is really no way to open it up to clean the senror. The dust is sitting directly on the sensor and the dark blotches it produces need to be manually removed from every photo that I want to look presentable, especially those with large areas of a single colour. That camera was itself a replacement for the first one I got, which had a defective flash that always fired at full power.

Today, my iPod simply stopped playing any sound in one ear. The iPod is also a replacement for the one I originally got, which would pause randomly and for no reason if it was not kept perfectly still. Hopefully, cleaning the jack for the headphones will fix this newer problem, because my experience of sending the first iPod back to Apple was hellish and the one they sent back (more than a month later) had a click wheel that was off kilter.

I wonder whether I have particularly bad luck with electronics or whether I am just pickier about them working properly and more willing to go through the hassle of getting them fixed. Both my Sony and Panasonic portable CD players got sent back to the manufacturer for defects. My GPS receiver is actually the replacement for a replacement. It’s grandfather had abysmal reception, even compared to other identical models, and its father died for no apparent reason during the second Bowron Lakes trip.

I should not, in any case, let these things distract me from the task of finishing my core seminar paper for tomorrow. It’s on whether order and justice are compatible in international relations. Obviously, it’s the kind of topic that anyone with normative concerns will feel fairly strongly about after five years of studying IR at the university level. That makes it both easier and harder to write upon. In the interests of not being up all night, I shall get back to it.

PS. This week’s readings on normative theory have been the first time I read a lot of Dr. Andrew Hurrell’s work. It has been really interesting, well written, and suited to my research interests. I think I will probably take normative theory as one of my two optional subjects next year. Overall, I think it meshes well with a research project focused on environmental politics.

PPS. It seems like it might actually be my headphones which are defunct. While they seemed to work in my iBook before, they do so now only when you hold them in a certain way. I will need to try out the iPod with another pair.

PPPS. Upon further experimentation, the problem lies with the headphones, not the jack on my iPod. While they work if you twist them in a certain way in the iBook socket, they don’t work at all in one ear with the iPod. I will need to buy new ones. In some sense, this is worse. At least the iPod is under warrenty, and all electronics are absurdly expensive here. I honestly can’t understand why people tolerate it. England desperately needs Walmart.

Music and frustration: copy protection schemes

Having spent the last few minutes explaining to a friend why a brand-new, legitimately purchased CD will not play in her computer due to the copy protection EMI has included, I am reminded of my considerable indignation about how the music industry is treating their customers. Yes, in this case, it was possible to disable the copy protection program just by holding shift as the CD was inserted into a Windows computer, but there is no guarantee at all that music you buy today is either usable or safe.

Having spent the last few minutes explaining to a friend why a brand-new, legitimately purchased CD will not play in her computer due to the copy protection EMI has included, I am reminded of my considerable indignation about how the music industry is treating their customers. Yes, in this case, it was possible to disable the copy protection program just by holding shift as the CD was inserted into a Windows computer, but there is no guarantee at all that music you buy today is either usable or safe.

In the worst case, such as the notorious Sony BMG rootkit, inserting a legitimate music CD into your computer intentionally breaks it. It also causes it to report what you listen to to Sony, even if you choose ‘no’ when a screen comes up asking for permission to install software. It also creates really sneaky back doors into your system that can be exploited for any number of purposes, by Sony or random others. While Sony is currently facing lawsuits for this particular, infamous piece of malware, it isn’t nearly enough to put my mind at ease. If some 16 year old had written something comparably dangerous, they would probably be in jail.

Legitimately downloaded music is little better. Songs you buy from the iTunes music store may work with your iPod today, but they won’t work with another portable player. They won’t even play in software other than iTunes, and there is no guarantee that they will still work at some point in the future. Spending a great deal of money on songs from there (and they’ve just had their billionth download), is therefore probably not very wise. You don’t actually own the music you are buying – you’re just buying the right to use it on someone else’s terms: terms that they have considerable freedom to change.

Personally, I will not buy any CD that contains copy protection software. I will not buy a Sony BMG CD, regardless of whether it does or not, nor will I be buying any of Sony’s electronics in the near future. This is a business model that needs to change.

Nuclear Test Sites

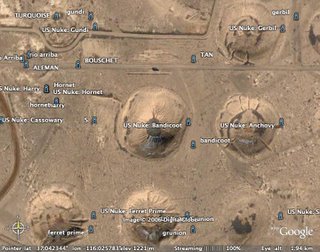

As we were both experimenting with Google Earth tonight, Neal pointed out an area in Nevada to me. You can see the crater where an atomic bomb in the 100 kiloton range was tested:

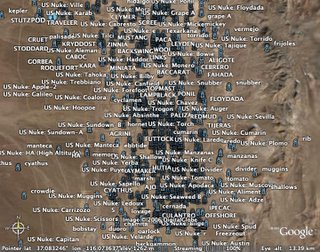

Surrounding it are more test sites:

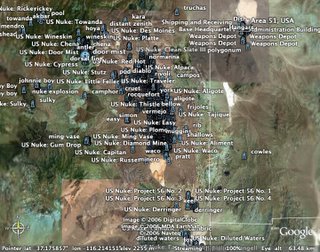

They sure felt the need to make sure these things would work:

It definitely makes you more certain that Eisenhower was on to something when he talked about a military-industrial complex in his farewell address:

In the words of Ike: “Every gun that is made every warship that is launched every rocket fired, signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed”

It really defies all belief, doesn’t it?

[Update: 5 November 2005] Here are some more of my posts on nuclear weapons.

An Oxford absurdity

According to Esther and Wikipedia, it seems that anyone who completes a BA or BFA at Oxford automatically gets a Master of Arts (MA) degree seven years after matriculating, for a nominal fee. According to Wikipedia: “Despite the fact that no greater academic achievement is involved, the MA remains the most important degree in Oxford.”

Since I won’t have done an undergraduate degree here, it seems as though I will never get one of these nominal MAs. As such, once I finish my degree I will have the 28th highest possible rank, and it will never increase. If I had done a BA here, seven years after matriculating I would have risen to the 12th highest rank (provided I went on to do an M.Phil), or the 18th highest, if I just left it at the BA. In either case, I would outrank: “Doctor of Medicine if not also a Master of Arts”

There are apparently 46 ranks of Oxford graduates, the top 18 of which can only be earned if you have one of these MAs, with the exceptions of Doctors of Divinity and Civil Law (not Medicine). Only those with this titular MA can become full members of the university. The highest Oxford academic rank: “Doctor of Divinity” and the lowest: “Bachelor of Education.”

Despite spending two years and an absurd amount of money, I will end up with a degree that is nominally less important than one you get automatically. Completely absurd.

Chapter 246: In which Milan demonstrates philosophical ineptitude

In the middle of the afternoon, I made a concerted effort to read the Heidegger paper that Tristan sent me a few weeks ago: The Question Concerning Technology. It was meant to be a contribution to my ‘discretionary reading on environmental politics related matter’ effort. I know it will annoy him to say that I found it mostly incomprehensible – in both approach and diction – but that is assuredly the fact of the matter. Heidegger goes on and on about Greek and the nature of silver chalices. While I am sure the example would be brilliantly illustrative if I had any idea of what he was talking about, it serves no purpose for me. It’s akin, I think, to someone who knows nothing about computers sitting down with a dense text on scripting and the UNIX command prompt.

Just as arcane knowledge of computers alienates you from everyone who does not have it – by stripping you of the ability to communicate as richly as you could if you were alike in ignorance – such knowledge leads to tremendous frustration whenever you deal with someone who has it in the opposite quantity. The computer geek is as frustrating and incomprehensible to the neophyte as the neophyte is to the geek. The knowledge that is a source of pride for the geek is often marked off as unnecessary to the neophyte, for whom it only serves an instrumental purpose: a purpose that can be achieved indirectly, by enlisting the aid of the geek. What enlisting the aid of philosophers means, exactly, I don’t know, but I consider much of philosophy to be marked off in the space of “information for others to deal with.”

This is not necessarily an embracing of ignorance, but perhaps more properly a response to the impossible vastness of knowledge and the sheer variety of dialects in which that knowledge is stored and discussed. It’s paradoxical, but ultimately obvious, that increased understanding of something can actually strip you of the ability to explain it or deal with people who don’t understand it. Attending lectures of someone who has colossal knowledge of a truly obscure field is among the best possible demonstrations of how knowledge is a cage.

Of course, when were talking about the physical sciences, there can be an external referent for expertise. I may not be able to understand what an engineer means when they talk about stress factors or the properties of metals, but I can see whether the bridge stays up or crashes down. Likewise, physicists and chemists can make predictions and develop technologies that demonstrate that their knowledge is – in some sense – correct. What comparable contribution can philosophers or, for that matter, international relations scholars make?

So much of what we do is like the nuances of a traditional Japanese tea ceremony: only those with considerable specific knowledge could ever know whether what was being performed was correct or merely a close approximation. No observer not steeped in the tradition could tell and, in a broad sense, the tradition itself is completely arbitrary. If we had all argued our way to some other equilibrium, it would serve exactly the same role as this one.

Of hair and housing

Another round in an ancient battle played out today. I mean, of course, the battle that has raged over the length of my hair. There is a camp that encourages it to become ever-longer: a camp served by apathy and thrift on my part, but opposed by my will. Short hair is manageable hair, which does not become an embarrassment if briefly slept upon or subjected to a hat. The viability of the hat option makes temperature control more feasible. In short, the advantages of short hair are legion. Of course, the longer-hair crowd always wins out in the short term, as the stuff extends day by day. I always win in the medium term, once I muster the energy to blast it back. The first red line is when it becomes capable of touching my eyes; the second when it begins sticking out over my ears; and the third when it starts behaving unpredictably on the back and sides of my head. By then, it has become a dangerous snarling mass.

When you think about it, winning in the medium term is the best we can ever hope for as human beings. I’m now probably mostly made of Oxford tap water, where once I was made of Vancouver tap water. My ability to continue rebuilding myself out of water and digestive biscuits is ultimately capped by entropy: the central reason for which we are all doomed in the end. As such, it if in the 5 to 50 year time scale that we have the opportunity to snatch what victories we may from the jaws of irrelevance.

Speaking of medium-term victories, Kai and I may have found a suitable flat for next year. It’s located right near St. Antony’s, on Church Walk. It’s farther from Sainsbury’s and the centre of town, but about the same distance from the Department, and closer to Jericho and some nice commercial areas. It’s a basement suite, located underneath some kind of institute. As such, there will be nobody upstairs to bother us or be bothered evenings and weekends. It also includes a sizable back yard: almost as large as all of Library Court. We could definitely hold some nice garden parties there. The three bedrooms all have safety windows looking outside at ground level. (The third bedroom would be occupied by our silent partner.) The kitchen looks good and even the smallest of the bedrooms would more than adequately serve me.

At £85 a week for the two large bedrooms and £75 a week for the small converted living room, it seems quite pricey. That said, my termly battels in Wadham have exceeded £900 for each term and inter-term break period. Having a better kitchen would also encourage me to eat in more often, as well as affording me the chance to actually store prepared food. Those prices include power, water, and broadband internet access (obviously the most vital of the three). In short, the flat itself is very nice with advantages of location and design.

The biggest potential problem has to do with availability. The lease runs from September to September, which is standard, but the three current residents are all moving out in April. They are looking for someone to serve out the rest of their lease, then take one on for next year. My accommodation in Wadham runs until the 17th of July, but I am inquiring as to whether I could move out before the start of Trinity Term instead. Then, I could live in the new flat from the start of April until our exams end in July 2007, at which point we would presumably find people to play the same lease-finishing role as we would be playing from April to September of this year.

This will be the first time I’ve actually lived in accommodation that is private to this extent. I say ‘to this extent’ because the building does belong to St. Antony’s College and it would be through them that we would be letting it. Even so, it is much closer to private accommodation than Library Court, Fairview, or Totem Park have been.

I am excited about the prospect of living there.

PS. The haircut, which I got from the same place on the Cowley Road as the last one, is neither the best nor the worst I’ve received. The best was in Venice and now comprises the picture I show to barbers; the worst was in London, and I am sure it’s now part of my CIA dossier. This one is slightly worse than the last haircut I got in Oxford.

Dead Wolf Marketplace

Up on South Parks Road, there is a sheet-metal covered barrier that is at least twelve feet high – topped with several strands of razor wire. In front, there are concrete blocks and along the top there are fixed and movable security cameras. This barricade is built around the Oxford Animal Lab, which hundreds of people have been protesting and which has gone through several building contractors because they keep getting scared off by death threats. The builders now wear balaclavas, for fear of being harassed when off the site.

Less than a kilometer away, as I was walking through the covered market in search of a shop where Louise told me I might find more kinds of tofu, I passed six dead wolves hanging from hooks. I was astonished. Six headless, fur-covered, quadrupedal corpses split down the middle and hanging along the edge of a pathway that people bustle down with bags of new shoes.

The obvious charge is one of hypocrisy, but my response to the dead creatures was nowhere near so rational. It was a shock and disgust that persists hours later – despite efforts to wash it away with organic cola (disgusting) and ciabatta with cheese and roast veggies.

Along with the rows of dead rabbits (their heads in plastic bags so as to help people avoid anthropomorphizing them), the quail, and all the rest of the meat, they produce a smell that permeates the whole market and that lingers in my nostrils. Colour me confirmed in my vegetarianism.

[Edited: 7:46pm] Having consulted a wolf expert in circumstances too strange to go into, the consensus if that the aforementioned quadrupeds are assuredly not wolves. My imperfect photos reveal fur that is the right colour, but legs that are decidedly too thick. Headless, they remain unidentified.

Still not FoodSafe, but much better

Over the course of an hour and a half this afternoon, Nora and I executed the kitchen cleanup. With freshly purchased Sainsbury’s bleach, anti-bacterial spray, and various abrasive implements, I set about rendering the inside of the fridge, the counters, and all other surfaces relatively free of grime and microorganisms. After fifteen minutes trying to remove the molasses-thick, 2mm layer of pure grease (decorated with dead and dessicated insects) atop the hood on the cooker, I gave up the attempt in favour of some braver soul who will come after me. Nora helped with the kitchen shelves, all the abandoned dishes, and much else. Nobody else turned up, despite every member of Library Court having to pass at least two signs advertising this several times a day.

Almost all of the food in the fridge – from the dark brown mayonnaise to the sausages that were best before November 1998 – has been discarded, as well as much of the putrified matter on shelves and in cupboards. Walking out into the night, the sky was dancing with lines of luminescence – probably the result of 90 minutes in an enclosed, non-ventilated environment with high concentrations of sodium hypochlorite and sodium hydroxide in the air.

Perhaps they will add a sparkle to the final version of my essay, before I march it over to Nuffield and return to finish up my Inuit presentation.

An orrery of errors

One of the trickiest questions of environmental politics is always whether we are actually managing to deal with problems, or whether we are just shifting them elsewhere – either spatially or temporally. This is true on many fronts: with regards to pollution, with regards to resources, and with regards to the overall intensity with which we are exploiting the earth. Our experiences of environmental conditions in the rich world are certainly not reflective of the overall global story, nor of the ultimate consequences.

Looking first at pollution: during the early periods of their industrialization, the countries that are now the world’s cleanest were polluted to the point of seriously impinging upon the health of those who lived within them, particularly in the cities. London’s notorious fogs were more the product of particulate matter from burning coal than the product of the natural humidity of the place. Some Japanese cities were so saturated with heavy metals from industrial sources that they became notorious for the illnesses and birth defects that resulted. Evidently, the bulk of these problems have now been overcome in the developed world. Zoning laws, environmental regulations, new technologies, and the rest have all come together to make our air and water broadly safer than they have been since the industrial revolution.

The extent to which we can cheer this is, however, mitigated somewhat in the knowledge that much of the health and safety we enjoy is the product of misery elsewhere. Consider the conditions in the industrializing regions of India or China. Consider the conditions in the various resource sectors that provide the raw materials of affluence: from coal and diamond mines to hazardous timber industries run by corrupt national armies and organized crime syndicates in the Asia Pacific.

Indeed, resources are probably the area where this outsourcing can be most obviously seen. What forests remain in much of the developed world are fairly rigorously protected. Even Canada’s vast timber industry has requirements for conservation, replanting, and the protection of streams. I am certainly not claiming that this industry is perfect, nor entirely sustainable in its present form, but it is clear that these kind of standards certainly do not exist worldwide. Where once the big area of concern among environmentalists was the Amazon rainforest in Brazil (certainly still in danger from a growing human population and the desire for land), the real, widespread damage being done today is in Asia: where the smoke from massive land-clearing forest fires occasionally rains down on cities and where Japan uses more tropical hardwood than any other nation in the world. The primary use: shaping concrete.

The most difficult to assess area in which such phenomena are occurring is in terms of just how much stress vital ecological and climatological systems can endure before they are degraded in the long term. I needn’t remind any long-term readers about the example of fisheries, but is also bears considering just how much toxic and radioactive sludge we can continue dumping into the sea before the problem comes back to bite us. Consider the dozens of Soviet nuclear warships and submarines that have been scuttled off obscure portions of the Russian coastline: both well-stuffed with spent fuel and other radioactive waste and, in most cases, themselves rendered dangerously radioactive. Like the concrete tomb in which the Chernobyl reactor has been encased, it is only a matter of time before these containers are broken down by time and corrosion.

A similar story of large scale pollution can be told about the atmosphere – and I am not talking about greenhouse gasses and climate change. A broad collection of chemicals including the products of burning garbage, as Japan does widely, industrial chemicals, like the PCBs leaking from the old RADAR stations along Canada’s Distant Early Warning Line, and pesticides have such chemical compositions that they break down only extremely slowly in the biosphere. They do, however, concentrate in fatty tissues and in ever-greater concentrations as they progress up the food chain. The long-term ramifications of these persistent organic pollutants are, naturally, far from entirely known.

As for climate change, this is the macro-level elephant in the room. While we don’t know exactly what it will involve, what magnitude it will be, and what it will cost to deal with, the reality of climate change demonstrates how human activity can impact the entire planet. It also underscores the extent to which our present prosperity may be banking colossal problems for future generations.

The point of this is not to be overly alarmist, nor to endorse specific policies for dealing with the above problems. The point is related to how problems need to reach a certain level of severity before action against them comes together. Look at the present political circuses about health care and pensions in all the demographically-shifting rich states. Sometimes, action taken at the point where danger is apprehended is effective. Look at the Montreal Protocol on chlorofluorocarbons: the major class of chemicals that was eroding the ozone layer. Within a couple of decades of the identification of the problem, a fairly effective international regime was in place to begin dealing with it. The ozone is recovering.

Looking through the literature, you will see the ozone example a lot. That’s not just because it is a fairly good example of international cooperation on a clear environmental problem: it’s because it is one of a few success stories among myriad failures. Hopefully, in the next few decades, we will gain tools to better understand the future consequences of present choices and actions. Likewise, I am hopeful that we will develop the wisdom – individual and collective – to begin curbing contemporary demands and wasteful and destructive contemporary practices, both with an eye to global equity and another towards those who are to succeed us on this planet.

- A batch of new photos has been added to my Photo.net portfolio, while I’ve been avoiding my half-finished essay on neo-liberal institutionalism for the core seminar. You can always get to my portfolio quickly from http://photo.sindark.com.