I don’t know exactly why, but the insomnia which has been my normal state of life for as long as I can remember has given over to what’s more like never-ending tiredness: going to bed tired, waking up tired, spending all day tired.

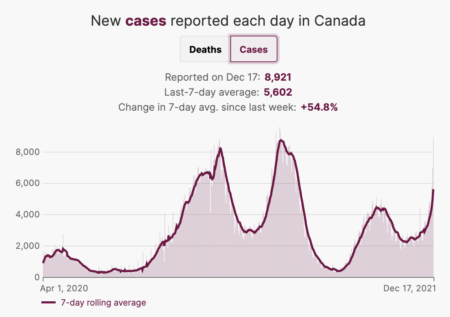

It may be from the loss of academic and social non-dissertation activities that give structure and variety to life, or just from the exhaustion of watching wave after pandemic wave crest and break while we collectively flounder. No doubt it comes partly from the rage of seeing the way in which we’re destroying our world, and yet our politics simply side-steps the issue as voters and lobbyists wedded to the status quo keep us cycling between political parties and leaders that match up their inadequate ambition with unserious implementation.

Maybe more than anything my own exhaustion reflects how everyone else seems to have been eroded and abraded: turning inward, turning silent. Maintaining any kind of social connection has jumped in difficulty, even though I suspect that most people could work to reduce their feelings of isolation and hopelessness by cultivating community in the ways which are possible without close physical presence.

I feel like I need something to lay down a boundary in time — or make one day or week seem different from another — to get back to a tempo of thesis work that will let me get the thing done before the university cuts me off irretrievably at the end of the year. And yet nothing of the sort is possible. I can’t reset the location, content, or cast of characters in my days, and so life feels like April 2020 made eternal.

I know it’s one of our worst human habits to develop the pattern of entitlement and resentment: growing to feel entitled to whatever good things we have happened to get, internalizing the notion that we have them as the result of merit or a just universe, and then cursing the injustice of losing it. The habit of mind we need to cultivate is that “nothing here is promised, not one day.” If we’ve ever had the good luck to experience something positive, we should see it as an unwarranted boon from a universe that is indifferent to all our notions of deserving or fairness, and if we should lose it we should hang on to the gratitude for having ever had it.

We’re all going to lose more than we can guess — maybe everything — as the full consequences of our fossil fuel civilization work their way through the planetary system. If our collective response to loss continues to be anger, resentment, and turning against each other, it’s hard to see how we will achieve the cooperation that has the sole prospect of saving us.

Related: