There are some comparatively convincing arguments for why fossil fuel divestment can’t do much to limit the severity of climate change, at least in terms of the direct effects from institutions selling their shares.

One important one is that people buying and selling stocks, and the changing value of the stocks, doesn’t directly profit or harm the company involved. A secondary market in shares is necessary to make IPOs possible, but once a company has gone public, it raises the money for big new fossil fuel projects in other ways, such as borrowing from banks.

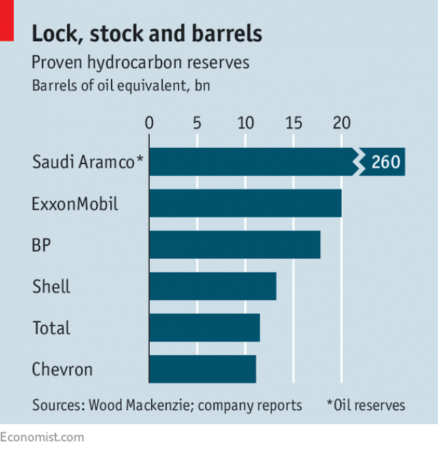

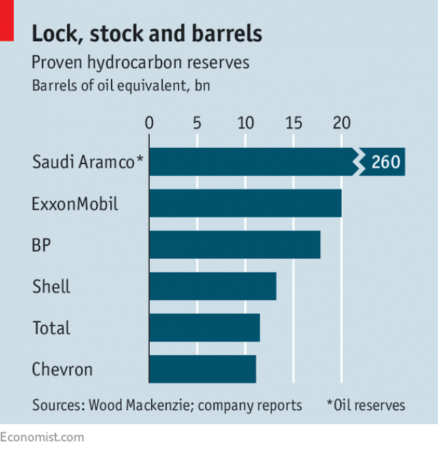

Another is that — while the proven reserves owned by companies like ExxonMobil are vast and can do considerable climate damage — sovereign countries have much larger reserves:

There are responses to these objectives, mainly in terms of how divestment is meant to gradually shift investor sentiment. Divestment is based on a financial as well as a moral case: if we really are going to control climate change, we can’t burn most of the world’s remaining coal, oil, and gas. As such, it makes no sense to develop big new projects, since we can’t even use all the resources in projects that have already been built. If it helps to spread that idea, divestment will have been worthwhile.

It might even help reduce the value of Saudi Aramco itself and the magnitude of its future investments, given that the firm is expected to be partly privatized in the near future.