I was fortunate to be born in a time and place where everyone told us to dream big; I could become whatever I wanted to. I could live wherever I wanted to. People like me had everything we needed and more. Things our grandparents could not even dream of. We had everything we could ever wish for and yet now we may have nothing.

Now we probably don’t even have a future any more.

Because that future was sold so that a small number of people could make unimaginable amounts of money. It was stolen from us every time you said that the sky was the limit, and that you only live once.

You lied to us. You gave us false hope. You told us that the future was something to look forward to. And the saddest thing is that most children are not even aware of the fate that awaits us. We will not understand it until it’s too late. And yet we are the lucky ones. Those who will be affected the hardest are already suffering the consequences. But their voices are not heard.

Is my microphone on? Can you hear me?

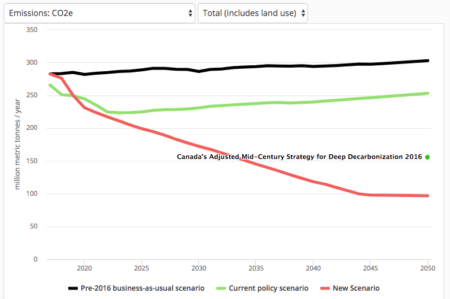

Around the year 2030, 10 years 252 days and 10 hours away from now, we will be in a position where we set off an irreversible chain reaction beyond human control, that will most likely lead to the end of our civilisation as we know it. That is unless in that time, permanent and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society have taken place, including a reduction of CO2 emissions by at least 50%.

And please note that these calculations are depending on inventions that have not yet been invented at scale, inventions that are supposed to clear the atmosphere of astronomical amounts of carbon dioxide.

Furthermore, these calculations do not include unforeseen tipping points and feedback loops like the extremely powerful methane gas escaping from rapidly thawing arctic permafrost.

Nor do these scientific calculations include already locked-in warming hidden by toxic air pollution. Nor the aspect of equity – or climate justice – clearly stated throughout the Paris agreement, which is absolutely necessary to make it work on a global scale.

We must also bear in mind that these are just calculations. Estimations. That means that these “points of no return” may occur a bit sooner or later than 2030. No one can know for sure. We can, however, be certain that they will occur approximately in these timeframes, because these calculations are not opinions or wild guesses.

These projections are backed up by scientific facts, concluded by all nations through the IPCC. Nearly every single major national scientific body around the world unreservedly supports the work and findings of the IPCC.

Did you hear what I just said? Is my English OK? Is the microphone on? Because I’m beginning to wonder.

She’s right. Even among advocates of climate action there has been a deep and long-running unwillingness to be honest about what controlling climate change requires and the suffering that will arise if it isn’t done.

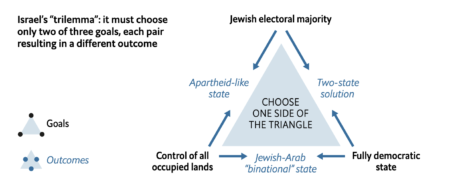

I think all the political leaders from this time (the carbon tax advocates and the clueless climate deniers) will be remembered as failures who had all the necessary information and technology but who still plunged humanity into the abyss because they were too controlled by the status quo to do otherwise.

Whether that abyss will just be a great amplification of the climate change effects we have already seen or something that challenges or destroys human civilization will depend on how quickly we can disempower the leaders holding us back and listen to people like Greta.