One major tenet of liberalism is the idea that greater awareness of the world gained by people collectively through science and individually through education can improve overall human welfare in the long term. Firstly, the idea is that people will gain a more accurate understanding of the world and how it works. Much more controversially, they might improve the way they reason.

A game much loved by economists illustrates the controversy:

There are two players. The first player is asked to divide $10 into two parts and offer one to the second player. If the second player accepts the offer, each player gets to keep their share. If the second player refuses, nobody gets anything.

Standard economic logic would call upon player one to offer exactly $0.01, which player two should happily accept. Both players are made better off and should thus be willing to make the deal, and each player has maximized their earnings, given the rules of the game.

Of course, the game doesn’t work this way with real people. Hardly anyone will accept an offer of less than $3. This is entirely logical if you view the game not as an isolated occurrence, but one event in a life. Over the course of a life, it pays to develop strategies that keep you from having advantage taken of you. Likewise, over the course of repeated interaction, it pays to have strategies by which other people can be compelled to give you a better deal. This one choice may not offer the scope for such development, but the existence of such heuristic devices (like rules of thumb) can be extremely efficient where people have limited information and thinking power.

Economists, on the other hand, are about the only people who make offers of less than $1. More tellingly, they are also about the only people who accept such meagre offers. Through exposure to economic theory, their mechanisms of logical thinking have been altered. It is probably fruitless to speculate on whether they have been improved. Economists can understand the importance of factors like those listed above, so playing this way isn’t obviously a sign that their thinking has worsened. Of course, if economic trailing makes them less likely to anticipate that people might reject a $0.01 offer, perhaps they are worse off overall.

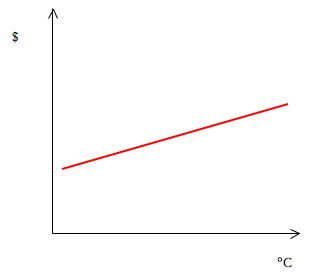

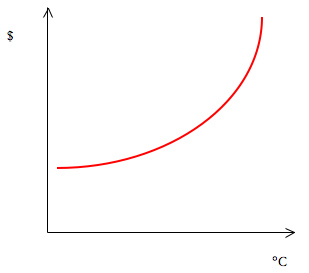

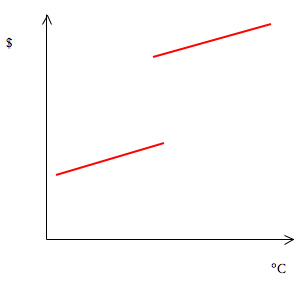

What is more interesting than the consideration of whether the economically optimal strategy is inferior or superior is the consideration of how frameworks of understanding affect decision-making and, furthermore, what effect that has on the liberal conception of welfare improvement through improved knowledge. The previous blog entry, for instance, portrayed the costs of global warming in terms of how much it would cost people to deal with (a very common economic representation). Drowned polar bears and damaged ecosystems only matter insofar as they affect people. Personally, I find such an approach reprehensible – for the same reason I think the wholesale denial of animal rights is morally unacceptable.

One can defend that position on pragmatic grounds: human beings with a reverence for nature have a better chance of living good lives and/or not wiping ourselves out. Saying we should cultivate the belief on those grounds is similar to Rorty’s conception of ironic liberalism. By contrast, the belief that the integrity of natural systems matters for its own sake has an intuitive appeal of a sort very un-chic and difficult to defend in a world full of poststructuralist rejections of firm ontological foundations to moral truth. Anyone who can devise an argument for the inherent value of nature not subject to such criticism will earn my appreciation.

PS. Inside nested padded envelopes, the dust-infested Canon A510 is en route to a registered service depot. If they decide to cover the problem under the warranty, I expect they will replace the camera outright, rather than trying to open and clean it. Doing so would take a fair amount of some technicians time and, if the camera isn’t properly sealed, it would only be a matter of time before parts of my sensor would start getting opaque again. Hopefully, it will come back in time for my trip to Ireland later this month.

PPS. I just upgraded to WordPress 2.0.4. Please report any bugs you come across on the bug reports page. Note also that, due to a barrage of spam comments, I have tightened the comment filtering settings. My apologies if any of your comments get zapped by the filters.