One common view of the nature of democracy is a system wherein a populace seeks to advance the common interest, either through direct participation in decision-making that affects everyone or through the election of representatives to do so. This view posits the existence of a universal interest that is beyond the sum of individual interests; the aim of government is to help to pull the reality of life closer to the kind of life that would be established through the realization of that universal good.

One major problem with this view is the possibility that, with a few exceptions, no such universal interest exists. We have a universal interest in not being exterminated, but it’s not clear that there is any such thing in the realm of social policy. An alternative view of the nature of democracy highlights its procedural characteristics, two of which I consider to be the most important: the division of power and oversight.

Democracy, viewed in this way, is a system of rules designed to limit the collection and arbitrary usage of power by individuals and groups. It recognizes the fundamental difficulty of this struggle, derived from the way in which most people given the opportunity to rule will try to use that power to perpetuate their influence. It likewise recognizes that authority in the absence of oversight leads inevitably to abuse, whether by corrupt politicians, unaccountable police, or an unconstrained army. The most important institutions within a democracy, then, are things like the rule of law, courts, regulatory bodies, a free press, and elections. The last of these serve less to select a group of representatives who have the right ideas about the universal good and more to rotate people often enough that they cannot escape the shackles that democracy is meant to impose upon them. When rulers do wriggle out of those bonds, the results are corruption, incompetence, and tyranny.

A procedural view of democracy does not assume the existence of a universal good – it just acknowledges that people have life projects of their own and, unconstrained, most are happy to trample all over the plans of others. The basic idea derives from the expression: “My right to swing my fist ends where your nose begins.” Unfortunately, plenty of people are happy to swing regardless. Only by constraining individuals in some ways – especially those in positions of power – can we have any hope of living our lives unmolested.

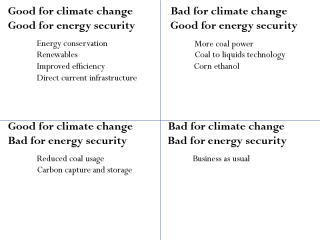

What, then, of social programs and all the efforts government makes to cajole and convince the populace of things? It is certainly possible that such cajoling can serve worthwhile ends, such as making people aware of previously unknown dangers. It can also serve far less universal ends: the promotion of the interests of one group through a devious appeal to a universal good. Arguably, much of politics is jostling between groups with narrow interests, seeking both to gain access to power and represent their personal interests as universal. This is exactly the kind of conduct a procedural democracy is meant to check: marrying empowerment within the sphere of individual agency with constraint in realms of inappropriate interference.

I am not willing to wholly disregard the possibility that democracies can develop projects based on the universal good, and perhaps even carry them out more effectively than other systems of government. What I am arguing is that such endeavours are a potentially valuable benefit of democracy, rather than its foundational justification. The aim is less to achieve the ‘best’ – a mode of thinking perhaps best suited to fascist states – but to moderate and avoid the worst. As such, when we abandon the principles of oversight and divided power, whether out of ambition or fear, we sacrifice a critical aspect of what it means to live in a democratic society.