If you listen to the speeches being made by presidential candidates in the United States, you constantly hear two ideas equated that are really quite independent: ‘energy security’ and climate change mitigation. The former has to do with being able to access different kinds of energy (natural gas, transportation fuels, electricity) in a manner consistent with the national interest of a particular state. The latter is about reducing the amount of greenhouse gasses emitted in the course of generating and using that energy.

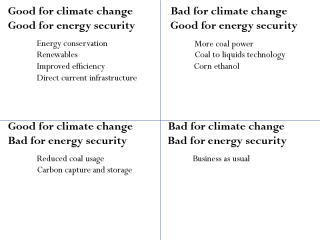

Some policies do achieve both goals: most notably, building renewable energy systems and the infrastructure that supports them. When the United Kingdom builds offshore wind farms, it serves both to reduce dependence on hydrocarbon imports from Russia and elsewhere and to reduce the link between British energy production and greenhouse gasses. Arguably, building new nuclear plants also serves both aims (though it has other associated problems).

There are plenty of policies that serve energy security without helping the problem of climate change at all. Indeed, many probably exacerbate it. A key example is Canada’s oil sands: they reduce North American dependence on oil imports, but at a very considerable climatic and ecological cost. Corn ethanol is probably an example of the same phenomenon, given all the emissions associated with intensive and mechanized modern farming. A third example can be found in efforts to convert coal to liquid fuel – a policy adopted during the Second World War by Germany and Japan when their access to imported oil was curtailed, but also an approach with huge associated greenhouse gas emissions.

Finally, it is possible to envision policies that help with climate change but do not serve energy security purposes. A key example is carbon capture and storage (CCS). Building power plants and factories that sequester emissions actually requires more energy, since it takes power to separate the greenhouse gasses from other emissions and pump them underground. If CCS technology allows the exploitation of domestic coal reserves without significant greenhouse gas emissions, both goals would be achieved, but CCS on its own contributes nothing to energy security.

The biggest danger in all of this is the unjustified muddling of two issues that are related but certainly not identical. It is simply not enough for developed states to ensure reliable and affordable access to fuels and power – they must do so in a way that helps to bring total global emissions in line with what the planet can absorb without suffering additional increases in mean temperature. Governments and private enterprises must not be allowed to pass off energy security policies with harmful climatic effects as ‘green.’