Ubiquitously, people use the left-right spectrum to sort people, political parties, and governments according to their political views. Like any model, it has its simplifications. At the same time, it is useful enough to be worth retaining.

That being said, this categorization can conceal important axes of disagreement. Not everyone on ‘the left’ or ‘the right’ agrees. For example, this is demonstrated by the vast differences between libertarians (generally considered right wing) and social conservatives. The former want to legalize drugs, allow gay marriage, and let people have whatever kind of sex they want. The latter sometimes want to lie to children to prevent sex and drug use, use scripture as inspiration for law, and preserve existing power structures.

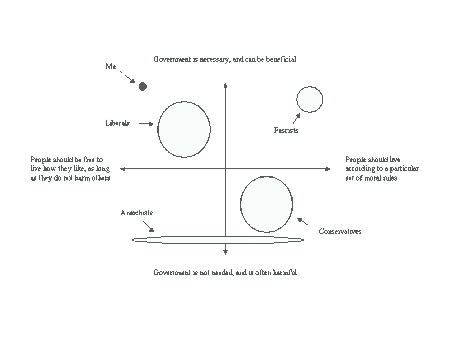

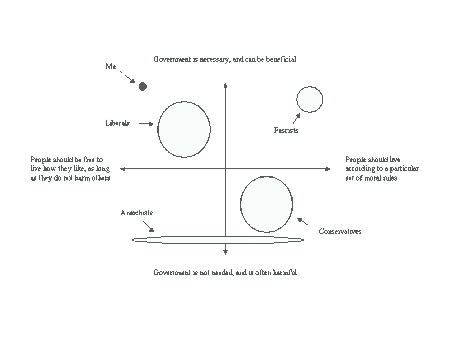

One more complex model that I think is useful takes two considerations into account:

- How necessary do you think government is? Can it be beneficial?

- How important are an individual’s own values, compared to those of their community?

On one axis, there is the range of views from ‘government is beneficial and absolutely essential’ to ‘government is harmful and not needed.’ On the other is an axis from ‘individuals should be free to live however they want’ to ‘people should live according to an external moral code’.

All combinations are possible. Anarchists agree that government is not needed and probably harmful, but disagree about whether we should all follow a particular ethical framework and, if so, what the framework should resemble. Some anarchists assume that – freed from government – people would probably arrange themselves into communistic little autonomous communities. Others prefer rather more militant notions of what anarchism might involve.

People of all political stripes disagree about the extent to which traditional or religious values should motivate how people behave, as well as the degree to which they are embedded in law. For instance, some people would like government to enforce morality by treating adultery as a criminal offence, or by criminalizing abortion, or by restricting the use of climate damaging fuels, or by forbidding companies from bribing public officials, etc, etc.

Of course, there is a big difference between enforcing ‘harm principle’ ethics, where only actions that damage unconsenting bystanders are restricted, and a more open-ended enforcement of morality by government. For people deeply concerned about how one person doing what they wish can prevent others from having the same freedom, government is often seen as an essential mechanism for preserving the overall liberty of everyone.

One element that is not well captured in this model is the range of different moral codes people want to see applied. These include everything from ‘traditional family values’ to various forms of religious fundamentalism to non-religious but dogmatic social philosophies like Ayn Rand’s Objectivism.

Still, I think this framework has some use, when it comes to understanding the range of political views that exist.

[Aside] To clarify my own view, I naturally recognize that governments can be extremely harmful: even oppressive to the point of murderousness. That being said, I think they are necessary because of how interconnected the world has become and, at their best, can do enormous good.