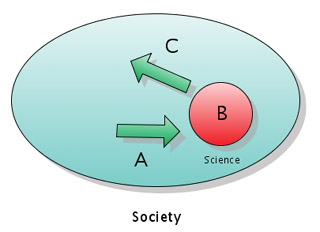

Partly motivated, perhaps, by frequent exposure to Hurrellean lists, I have been thinking about elements of the thesis in categorical terms. My head, therefore, is swimming with Venn Diagrams. Today’s ponderings have been about the roles played by scientists. I have come up with three headings:

- Investigative

- Deliberative

- Regulatory

The first is their traditionally conceived role, with the latter two serving as necessary modulating adjuncts.

Investigative

This is your standard ‘scientist peering down a microscope / examining RADAR images / performing Fourier Transforms‘ role. Within it, there are components related to discovery and components related to refining existing hypotheses. This is true both when science is behaving as evolutionary gradualists would predict (slowly making LEDs brighter and more power efficient) and during periods of punctuated equilibrium (think of the development of quantum theory, explaining those LEDs, and of Kuhn).

When it comes to the environment, important scientific behaviours mostly have to do with studying interactions. How does the combination of GHG emissions and particular emissions affect mean global temperature? How does the evaporation rate of Lake Nasser affect the marine ecosystems of the Mediterranean?

Deliberative

The difference between deliberative and regulatory is partly akin to the difference between safety and security. Safety has to do with protecting against non-malicious risks. A lightning rod is a safety device – unless you believe in a vengeful deity. Security has to do with addressing threats from active attackers. The same distinction exists when it comes to scientific integrity. Someone might make an undetected experimental error and come up with data that is incorrect; some early satellite measurements of global temperature were like this. Someone else might be in the pocket of a group with a vested interest in denying climate change, and might thus be working with an experimental agenda of muddying the waters.

The deliberative role of scientists, in an ideal community, is a mechanism for dealing with non-malicious disagreement. Experiments that are outlying can be examined and replicated, the reasons for the unexpected results identified. Theories can be developed and debated in the face of evidence.

Unlike the investigative role, which can be performed perfectly well by lone scientists in igloos on Baffin Island, counting the amount of lichen per square metre outside, this role is fundamentally social. It strikes at the important distinction between science as a set of procedures and ideals, scientists as actors who try to apply them, and the scientific community as an epistemic grouping.

On a side note: it does seem possible for a scientist to be generally strong on the investigative side, but very weak on the deliberative side. Richard Dawkins comes immediately to mind. What is wrong with his positions is much less the empirical basis of most of his claims, and much more the structures of argumentation that he tries to use to assert them. For deliberation to be a useful exercise, it cannot be entirely self-confident and closed to alternative perspectives. It is also important for it to be aggressive in terms of analysis, not in terms of attacking people – an ugly trait that Professor Dawkins has revealed more and more as his anger overwhelms his judgement.

Regulatory

I see the regulatory role as being two-fold. The first part is akin to security, as discussed above. It is the process of trying to separate the quacks from those who have genuine reasons and data behind their position. This is naturally an imperfect process, but it is something that the scientific community must engage with if it is to remain a ‘community’ in any meaningful way. A meaningless community, by contrast, would be one with ties only on the basis of common obscure knowledge or some kind of internal system of controls not based on seeking correspondence between scientific explanation and physical reality.

The other side of the regulatory role has to do with generating institutional structures. Issues like funding, the prioritization of research, and the like fall into this category. This is important, partly because it relates closely to the mechanisms by which quackery is identified. Whether or not the common historical perspective on Galileo as a correct person immersed in a structure of incorrect people is correct, it demonstrates the possibility that the mechanisms of scientific deliberation and regulation could be enforcing incorrect ideas. Avoiding this requires avoiding excess rigidity – a topic that arises frequently in the Lomborg debate, and with wide-ranging implications.

I would be especially keen to hear what any scientists reading this think of the above (real, labcoat-wearing scientists, not IR scholars with extensive statistical faith). If you don’t care to comment, perhaps you could just indicate in some unobtrusive way that there are actually a few people with scientific training who have been reading my mutterings from time to time. I know for sure about one. Naturally, non-scientists are encouraged to comment, as well.

PS. If you want an example of how ad hominem attacks are more likely to make you look stupid than correct, have a look at the latest disingenuous malarky from the Competitive Enterprise Institute. Never mind that carbon offsets have been used to offset the emissions related to An Inconvenient Truth, just look at the non-sensical progression of numbers on their little counters.