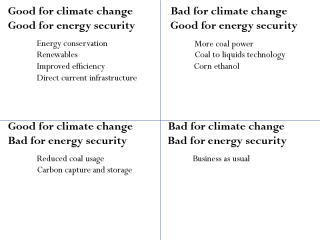

One limitation of renewable sources of energy is that they are often best captured in places far from where energy is used: remote bays with large tides, desert areas with bright and constant sun, and windswept ridges. In these cases, losses associated with transmitting the power over standard alternating current (AC) power lines can lead to very significant losses.

This is where high voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission lines come in. Originally developed in the 1930s, HVDC technology is only really suited to long-range transmission. This is because of the static inverters that must be used to convert the energy to DC for transmission. These are expensive devices, both in terms of capital cost and energy losses. With contemporary HVDC technology, energy losses can be kept to about 3% per 1000km. This makes the connection of remote generating centres much more feasible.

HVDC has another advantage: it can be used as a link between AC systems that are out of sync with each other. This could be different national grids running on different frequencies; it could be different grids on the same frequency with different timing; finally, it could be the multiple unsynchronized AC currents produced by something like a field of wind turbines.

Building national and international HVDC backbones is probably necessary to achieve the full potential of renewable energy. Because of their ability to stem losses, they can play a vital role in load balancing. With truly comprehensive systems, wind power from the west coast of Vancouver Island could compensate when the sun in Arizona isn’t shining. Likewise, offshore turbines in Scotland could complement solar panels in Italy and hydroelectric dams in Norway. With some storage capacity and a sufficient diversity of sources, renewables could provide all the electricity we use – including quantities sufficient for electric vehicles, which could be charged at times when demand for other things is low.

With further technological improvements, the cost of static inverters can probably be reduced. So too, perhaps, the per-kilometre energy losses. All told, investing in research on such renewable-facilitating technologies seems a lot more sensible than gambling on the eventual existence of ‘clean’ coal.