Category: Bombs and rockets

Military matters and state security: the hard-edged kind of international relations

Lego Space Shuttle Discovery and shuttle from Women of NASA set

Lego Space Shuttle Discovery deploying Hubble Space Telescope

Lego Women of NASA

Nancy Grace Roman with the Hubble Space Telescope; Mae Jemison and Sally Ride with the Space Shuttle; and Margaret Hamilton with listings of the software she and her MIT team wrote for the Apollo Program

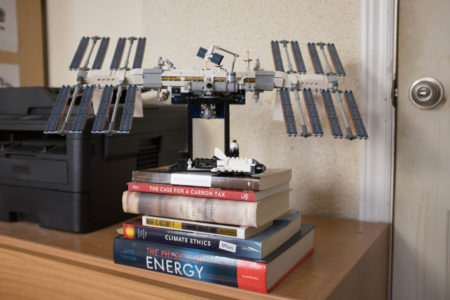

Lego ISS

Our psychological vulnerability to the con

In the 1950s, the linguist David Maurer began to delve more deeply into the world of confidence men than any had before him. He called them, simply, “aristocrats of crime.” Hard crime—outright theft or burglary, violence, threats—is not what the confidence artist is about. The confidence game—the con—is an exercise in soft skills. Trust, sympathy, persuasion. The true con artist doesn’t force us to do anything; he makes us complicit in our own undoing. He doesn’t steal. We give. He doesn’t have to threaten us. We supply the story ourselves. We believe because we want to, not because anyone made us. And so we offer up whatever they want—money, reputation, trust, fame, legitimacy, support—and we don’t realize what is happening until it is too late. Our need to believe, to embrace things that explain our world, is as pervasive as it is strong. Given the right cues, we’re willing to go along with just about anything and put our confidence in just about anyone. Conspiracy theories, supernatural phenomena, psychics: we have a seemingly bottomless capacity for credulity. Or, as one psychologist put it, “Gullibility may be deeply ingrained in the human behavioral repertoire.” For our minds are built for stories. We crave them, and, when there aren’t ready ones available, we create them. Stories about our origins. Our purpose. The reasons the world is the way it is. Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty or ambiguity. When something doesn’t make sense, we want to supply the missing link. When we don’t understand what or why or how something happened, we want to find an explanation. A confidence artist is only to happy to comply—and the well-crafted narrative is his absolute forte.

Konnikova, Maria. The Confidence Game. Why We Fall for It… Every Time. Penguin Books, 2016. p. 5-6

Ali Soufan’s view of 2020 security threats

The International Spy Museum hosted a great discussion with former FBI special agent Ali Soufan, author of two books about Al Qaeda:

It covers the post-2001 debate around torture for interrogation, questions of accountability in the use and disclosure of classified intelligence, and includes some interesting remarks about cooperation with international intelligence agencies, as well as relations and views between the CIA and the FBI.

The solar system’s other water worlds

I have mentioned Europa and Enceladus, moons of Jupiter and Saturn, as being among the most intriguing bodies in the solar system, since their liquid oceans create the potential that life could exist or survive there. Now we know that the dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, also has an extensive reservoir of brine beneath the surface.

Any would be a fascinating target for scientific exporation, though with the crucial caveat that it would require better planetary protection techniques to prevent them from being colonized by organisms from Earth which might take over in any habitable niche and which could even exterminate extraterrestrial life. We now believe that despite efforts to sterilize them spacecraft on the moon and Mars likely harbour viable life forms from Earth. That may not pose much of a risk in a hostile environs with a thin or absent atmosphere and merciless radiation, but it must be among the central concerns for any mission which will visit a body with liquid water.

The success of bin Laden’s strategy

Although al-Qaeda was unvanquished it was also unable to repeat its startling triumph. America was sinking ever more deeply into unpromising, fantastically expensive wars in the Muslim world—following the script that had been written by bin Laden. Repeatedly, he had outlined his goal of drawing America into such conflicts with the goal of bleeding the U.S. economically and turning the War on Terror into a genuine clash of civilizations. His attacks, from the twin U.S. Embassy bombings in East Africa in 1998, to the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000, and ultimately to 9/11, were designed to goad the United States into Afghanistan, where he expected that America would experience the same catastrophe that befell the Soviet Union in 1989, when it withdrew in defeat and then simply fell apart. Bin Laden’s plan was that the sole remaining superpower would dissolve, the United States would become disunited states, and the way would be open for Islam to regain its natural place as the dominant force in the world.

Ten years after 9/11, al-Qaeda is not defeated. It has shown itself to be an adaptable, flexible, evolutionary organization, one that has outlasted most terrorist enterprises in history. One day, al-Qaeda will disappear, as all terrorist movements eventually do. But the template of asymmetrical warfare and mass murder that bin Laden and his confederates have created will inspire future terrorists flying other banners. The legacy of bin Laden is a future of suspicion, grief, and the loss of certain liberties that are already disappearing from memory.

Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. Vintage Books, 2007, 2011. p. 428–9

The Iraq war and al-Qaeda’s second incarnation

The fateful decision of the Bush administration to invade and occupy Iraq in 2003 revivified the radical Islamist agenda. Simultaneous wars in two Muslim countries lent substance to bin Laden’s narrative that the West was at war with Islam… Although bin Laden and his cohort were essentially reduced to virtual presences on the Internet and smuggled tape recordings, the apocalyptic al-Qaeda took root, not only in Muslim countries but also among Muslim communities in the cities of Europe and eventually even the United States.

As early as 1998, following the bombing of the American embassies in East Africa, al-Qaeda strategists began envisioning a less hierarchical organization than the one that bin Laden, the businessman, had designed. His al-Qaeda was a top-down terrorist bureaucracy, but it offered its members health care and paid vacations—it was a good job for a lot of rootless young men. The new al-Qaeda was entrepreneurial, spontaneous, and opportunistic, with the flattened structure of street gangs—what one al-Qaeda strategist, Abu Musab al-Suri, termed “leaderless resistance.” Such were the men who killed 191 commuters in Madrid, on March 11, 2004, and the bombers in London on July 7, 2005, who killed fifty-two people, not counting the four bombers, and injured about seven hundred. The relationships of these emulators to the core group of al-Qaeda was tangential at best, but they had been inspired by its example and acted in its name. They were tied together by the Internet, which offered them a safe place to conspire. Al-Qaeda’s leaders began supplying this new, online generation with a legacy of plans, targets, ideology, and methods.

Meantime, the War on Terror was transforming Western societies into security states with massive intelligence budgets and intrusive new laws. The American intelligence community became even more deeply entrenched with the worst despots of the Arab world and grimly mirrored some of their most appalling practices—indiscriminate and often illegal arrests, indefinite detentions, and ruthless interrogation techniques. That reinforced al-Qaeda’s allegations that such tyrants only existed at the whim of the West and that Muslims were under seige everywhere because of their religion.

Wright, Lawrence. The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. Vintage Books, 2007, 2011. p. 425–6