This briefing on the militarization of space is very interesting. It is especially good insofar as it describes the special situation of the United States in relation to space and warfare, the consequences of the recent Chinese test of an anti-satellite missile, and some of the practicalities involved in tracking space debris and keeping satellites away from it.

Category: Bombs and rockets

Military matters and state security: the hard-edged kind of international relations

Why the Allies Won

Among the hundreds of books I read at Oxford, Richard Overy’s Why the Allies Won stood out as an especially engaging piece of historical argumentation. It is one of a handful of books I was determined to re-read when I had more time available. Given the fundamental importance of the Second World War in the establishment of the contemporary international system, the question is a rather important one. Overy’s explanation is well-argued, convincing, and consistently interesting.

This complex book has a number of general themes, each of which is based around a necessary but insufficient cause for the victory of Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union over Germany, Italy, and Japan. Overy goes into detail on the Battle of the Atlantic – particularly the importance of American supplies for Britain, the U-boat menace, and the tactics that turned the tide in that theatre. He likewise covers the war on the eastern front: from early German successes to the battles at Stalingrad and Kursk that marked the watershed point of the war. In the Pacific theatre, he does an excellent job of explaining the significance of the Battle of Midway, including the considerable role luck played in the victory. The outcome was largely decided by ten bombs in ten minutes that struck Japanese aircraft carriers while they were refueling their air wings.

An entire chapter is devoted to the cross-channel invasion from Britain into occupied France. Of particular interest is the role played by intelligence, a subject Overy arguably neglects to some extent in other circumstances. The ways in which the Allies kept German defences spread out through misdirection make for especially interesting reading.

Overy also covers more thematic reasons for the Allied victory: mass production, especially in the United States and Soviet Union; technology, especially air power; the surprising unity between the Allies; and the moral contest between the Allied and Axis states. Unlike many historians, he highlights Allied bombing as an effective military strategy. He remains ambiguous about whether the military utility justified the bombing of German and Japanese civilians, but argues relatively persuasively that attacks on oil facilities and other key bits of industrial infrastructure served an important strategic purpose.

Midway is not the only example of good fortune Overy highlights – partially in an attempt to undermine the argument that the war could only have ended the way it did. Adding external fuel tanks to the fighters escorting bombers into German airspace dramatically reduced losses, substantially bolstering the effectiveness of the strategic bombing campaign. Likewise, equipping a few aircraft to close a small ‘Atlantic gap’ helped secure the end of the U-boat threat. Even the devastating trap sprung by the Soviets upon the German supply lines approaching Stalingrad could not have succeeded without the incredible success of a few thousand isolated troops occupying the entire German 6th army.

This book is enthusiastically recommended to anyone with an interest in military history generally or the Second World War in particular. It is also a good general disproof of the idea that the outcome of wars is decided by basic material facts like the relative sizes of economies, or the idea that there aren’t decisive turning points in history where the world is pressed along one path as another is closed off.

Energy security and climate change

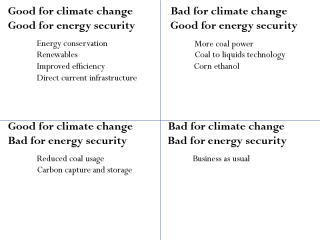

If you listen to the speeches being made by presidential candidates in the United States, you constantly hear two ideas equated that are really quite independent: ‘energy security’ and climate change mitigation. The former has to do with being able to access different kinds of energy (natural gas, transportation fuels, electricity) in a manner consistent with the national interest of a particular state. The latter is about reducing the amount of greenhouse gasses emitted in the course of generating and using that energy.

Some policies do achieve both goals: most notably, building renewable energy systems and the infrastructure that supports them. When the United Kingdom builds offshore wind farms, it serves both to reduce dependence on hydrocarbon imports from Russia and elsewhere and to reduce the link between British energy production and greenhouse gasses. Arguably, building new nuclear plants also serves both aims (though it has other associated problems).

There are plenty of policies that serve energy security without helping the problem of climate change at all. Indeed, many probably exacerbate it. A key example is Canada’s oil sands: they reduce North American dependence on oil imports, but at a very considerable climatic and ecological cost. Corn ethanol is probably an example of the same phenomenon, given all the emissions associated with intensive and mechanized modern farming. A third example can be found in efforts to convert coal to liquid fuel – a policy adopted during the Second World War by Germany and Japan when their access to imported oil was curtailed, but also an approach with huge associated greenhouse gas emissions.

Finally, it is possible to envision policies that help with climate change but do not serve energy security purposes. A key example is carbon capture and storage (CCS). Building power plants and factories that sequester emissions actually requires more energy, since it takes power to separate the greenhouse gasses from other emissions and pump them underground. If CCS technology allows the exploitation of domestic coal reserves without significant greenhouse gas emissions, both goals would be achieved, but CCS on its own contributes nothing to energy security.

The biggest danger in all of this is the unjustified muddling of two issues that are related but certainly not identical. It is simply not enough for developed states to ensure reliable and affordable access to fuels and power – they must do so in a way that helps to bring total global emissions in line with what the planet can absorb without suffering additional increases in mean temperature. Governments and private enterprises must not be allowed to pass off energy security policies with harmful climatic effects as ‘green.’

History in the news

The Bhutto assassination and the ongoing instability in Pakistan provides one of those situations where we see history unfurling hour by hour in front of us. At one level, it sharpens one’s appreciation for how one action or one individual in one situation can alter outcomes. At another, it reminds one of how dynamic history is, in broad sweeps.

Inheriting the world and beginning to understand it is one thing – having the imagination to anticipate the ways in which whole societies and groups of nations will evolve and interact is quite another.

Conditional support for our troops

Walking through the Rideau Centre yesterday, I came upon a cart selling t-shirts with various slogans on them. Beside the silly Che Guevara stuff was one shirt that caught my attention. In white letters on a red background it said “Support our Troops.” Under that were both a maple leaf and the flag of the United Nations.

It struck me as admirably post-nationalistic. We recognize the sacrifices made by members of the armed forces, but also that their conduct needs to be bounded by international law. While the sentiment is admirable, it sits uncomfortably with the reality of how ignorant most Canadians seem to be about what we are doing in Afghanistan. People really think we are mostly building bridges and distributing big bags of rice. The reality of the all-out war in which we are committed is very different.

That is not necessarily to say that we shouldn’t be fighting the Taliban along with our NATO allies; it is simply to highlight that Canadian governments manipulate the perception of Canada as a ‘peacekeeping nation’ to keep people from looking too closely at what our armed forces really do. The degree to which many people seem happy to continue to believe in the peacekeeping myth just because it makes them feel good is also problematic.

A few thoughts on climate justice

A couple of articles at Slate.com address the issue of ‘climate justice.’ This is, in essence, the question of how much mitigation different states are obliged to undertake, as well as what sort of other international transfers should take place in response to climate change. The issue is a tricky one for many reasons – most importantly because anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions constitute a unique experiment that can only be conducted once. If we choose the wrong collection of policies, all future generations may face a profoundly different world from the one we inherited.

If we accept Stern’s estimate of a five gigatonne level for sustainable global emissions, that works out to about 760kg of carbon dioxide equivalent per person on Earth. Releasing just 36kg of methane would use up an entire year’s allotment, as would just 2.5kg of nitrous oxide. One cow produces about 150kg of methane per year. Right now, Canada’s per-capita emissions are about 24,300kg, when you take into account land use change. American emissions are about 22,900kg while those of India and China are about 1,800kg and 3,900 respectively. Because of deforestation, Belize emits a startling 93,900kg of CO2e per person.

The questions of fairness raised by the situation are profound:

- Should states with shrinking populations be rewarded with higher per capita emissions allowances?

- Should states with rising populations likewise be punished?

- Should developing states be allowed to temporarily overshoot their fair present allotment, as developed states did in the past?

- To what extent should rich states pay for emissions reductions in poor ones?

- To what extent should rich states pay for climate change adaptation in the developing world?

It may well be that such questions are presently unanswerable, by virtue of the fact that answers that conform with basic notions of ethics clash fundamentally with the realities of economic and political power. We can only hope that those realities will shift before irreversible harmful change occurs. Remember, cutting from 24,600kg to 760kg per person just halts the increase in the atmospheric concentration of CO2. The level of change that will arise from any particular concentration remains uncertain.

Another vital consideration is how any system of international cooperation requires a relatively stable international system. While it is sometimes difficult to imagine countries like China and the United States voluntarily reducing emissions to the levels climatic stability requires on the basis of a negotiated international agreement, it is virtually impossible to imagine it in a world dominated by conflict or mass disruption. It is tragically plausible that the effects of climate change could destroy any chance of addressing it cooperatively, over the span of the next thirty to seventy years.

Entertaining physics demonstrations

His name is Julius Sumner Miller and physics is his business.

For those who lacked my good fortune in seeing most of these demonstrations a number of times at Vancouver’s Science World, the videos should give a sense of how physics can be made universally comprehensible and exciting. The facts that Mr. Miller looks like a mad scientist and that he has a penchant for hyperbole may well contribute to his ability to hold one’s attention.

My involvement as a camper and leader at SFU’s Science Alive daycamp also impressed upon me the effectiveness of physical demonstrations in sparking children’s interest in science. That is especially true when the demonstrations involve rapid projectile motion, strong magnets, cryogenic materials, aggressive combustion, and explosions.

The eradication of smallpox

On this day in 1979, the World Health Organization certified that smallpox had been eliminated from the wild. It was probably the only intentional extinction in human history, and it was a considerable boon to the human race. The disease is an atrocious one, and it took a heavy toll across history. Notably, it caused much of the death associated with the arrival of Europeans in North America.

The extinction raises a number of questions. One is whether it will ever be repeated. We came close with polio. Very few people would mourn the elimination of tuberculosis, malaria, or AIDS. Worldwide eradication requires global coordination – something very hard to bring about when territories exist outside the control of any state. Think of the tribal areas bordering Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Another issue has to do with smallpox itself. It was horrifically destructive to the First Nations because they lacked any of the immunity conferred by prior exposure. Now, the whole world is in essentially the same boat. An intentional or accidental release of the weaponized smallpox produced by many states could thus cause of devastating global pandemic. It rather makes one wish we had never turned it into a weapon in the first place.

‘Green’ fuel for military jets

There has recently been a fair bit of media coverage discussing an announcement from the United States Air Force that they are trying to use 50% synthetic fuel by 2016. The Lede, a blog associated with the New York Times, seems to misunderstand the issue completely. They are citing this as an example of the Air Force “trying to be true stewards of the environment.” There is no reason for which synthetic fuels are necessarily more environmentally friendly than petroleum; indeed, those made from coal are significantly worse.

The actual fuel being used – dubbed JP-8 – is made from natural gas. Air Force officials say they eventually intend to make it from coal, given that the United States has abundant reserves. This inititative is about symbolically reducing dependence on petroleum imports, not about protecting the environment. The German and Japanese governments did the same thing during the Second World War, when their access to oil was restricted. Furthermore, it is worth stressing that efforts by militaries to be greener are virtually always going to be window dressing. The operation of armed forces is inevitably hugely environmentally destructive: from munitions factories to test ranges to the wanton fuel inefficiency of aircraft afterburners, the whole military complex is about as anti-green as you can get.

People should be unwilling to accept superficial claims that installing some solar panels and building hybrid tanks is going to change that.

SONAR and modern naval warfare

Arguably, submarines are the greatest threat to a modern carrier battle group. Aircraft can be detected at long range using over the horizon RADAR and picket ships. Subs generally need to be located using SONAR, though magnetic anomaly detection can sometimes locate them as well.

Warm surface waters are separated from the chilly bulk of the ocean by a layer called the themocline. The fact that this layer reflects sound makes SONAR based detection across it highly challenging: especially when the contact is something as quiet as a modern hunter-killer submarine. It is possible to use active sonar (the pinging thing from movies), but the sound produced by such systems reveals your position to others for a distance ten times greater than the effective detection range of the device. It also horribly damages the ears of whales, especially when used at crazy amplitudes like 250 decibels.

One way to deal with the thermocline problem while still using undetectable passive SONAR is to use a towed variable depth sonar array. For a ship, that would be pulled along beneath the thermocline. For a sub, it would probably be deployed above the layer. Another approach is to exploit convergence zones. Because of the nature of water under pressure, sound gets reflected off the ocean floor and back to the surface at intervals of 61 km. Sounds originating in one place can thus be best detected at points forming concentric circles.

Problems with SONAR are much worse in shallow waters, where high levels of noise from animals, waves, and tide noise make passive SONAR pretty useless. As such, modern navies avoid such waters as much as possible and behave as though they have already been detected by enemy forces whenever forced to operate within them.