Category: Art

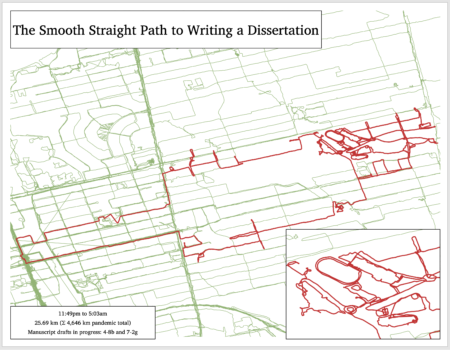

Exercise walk after another step toward the next draft

The fine points of minuting meetings

The British comedic TV series’ Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister — as well as being extremely funny — make some acute and accurate points about politics. One quote from the episode “The Quality of Life” is an arguably cynical, arguably tragically accurate summary of the relationship between civil servants and politicians.

Today, while pondering how to interpret some specific bits of activist decision-making and analysis, I was reminded of another gem from series 2 of YPM: “Official Secrets:”

Bernard Woolley: The problem is, the prime minister did try to suppress the chapter, didn’t he?

Sir Humphrey Appleby: I don’t know. Did he?

BW: Well, didn’t he? Don’t you remember?

HA: What I remember is irrelevant Bernard. If the minutes don’t say that he did, then he didn’t.

BW: So you want me to falsify the minutes?

HA: I want nothing of the sort! It’s up to you Bernard, what do you want?

BW: I want to have a clear conscience.

HA: A clear conscience?

BW: Yes!

HA: When did you acquire this taste for luxuries? Consciences are for politicians, Bernard! We are humble functionaries whose duty it is to implement the commands of our democratically elected representatives. How could we possibly be doing anything wrong if it has been commanded by those who represent the people?

BW: Well, I can’t accept that, Sir Humphrey, “No man is an island.”

HA: I agree Bernard! No man is an island, entire of itself. And therefore, never send to know for whom the bell tolls. It tolls for thee, Bernard!

BW: So what do you suggest, Sir Humphrey?

HA: Bernard, the minutes do not record everything that was said at a meeting do they?

BW: Well, no, of course not.

HA: And people change their minds during a meeting, don’t they?

BW: Well, yes.

HA: So the actual meeting is a mass of ingredients for you to choose from.

BW: Oh, like cooking.

HA: Like, no, not like cooking. Better not to use that word in connection with books or minutes. You choose from a jumble of ill-digested ideas a version which represents the prime minister’s views as he would, on reflection, have liked them to emerge.

BW: But if it’s not a true record…

HA: The purpose of minutes is not to record events, it is to protect people. You do not take notes if the prime minister says something he did not mean to say — particularly if it contradicts something he has said publicly. You try to improve on what has been said, put it in a better order. You are tactful.

BW: But how do I justify that?

HA: You are his servant.

BW: Oh, yes.

HA: A minute is a note for the records and a statement of action if any that was agreed upon. Now, what happened at the meeting in question?

BW: Well, the book was discussed and the solicitor general advised there were no legal grounds for suppressing it.

HA: And did the prime minister accept what the solicitor general had said?

BW: Well, he accepted the fact that there were no legal grounds for suppression… but

HA: He accepted the fact that there were no legal grounds for suppression. You see?

BW: Oh!

HA: Is that a lie?

BW: No

HA: Can you write it in the minutes?

BW: Yes

HA: How’s your conscience?

BW: Much better! Thank you Sir Humphrey.

Or, as put later by Linton Barwick in the 2009 satirical film “In the Loop“:

Linton Barwick: Get a hold of those minutes. I have to correct the record.

Bob Adriano: We can do that?

LB: Yes, we can. Those minutes are an aide-mémoire for us. They should not be a reductive record of what happened to have been said, but they should be more a full record of what was intended to have been said. I think that’s the more accurate version, don’t you?

Obviously in these cases there is a clear political purpose being served in presenting the minutes a particular way, but the problem of interpretation is intractable even with no such agenda. Humphrey is quite right to say that minutes which are not verbatim require decisions from the person writing them, and it is as true in political conversations as in talks between friends or lovers that people who take part in the same conversation can come away from it with quite different recollections about what each party tried to say and what was decided.

Tug-of-war sculpture

Podcasts and audiobooks

Because the spoken word content on Spotify is so-so most of the time (aside from podcasts like Ologies and the Spycast), I have been trying Audible to provide better quality listening material during walks.

So far I have finished James Donovan’s book “Strangers on a Bridge: The Case of Colonel Abel” about the espionage trials and eventual prisoner exchange of a KGB colonel living as an illegal in New York (also depicted in the excellent film Bridge of Spies) and Lyndsay Faye’s “Dust and Shadow: An Account of the Ripper Killings by Dr. John H. Watson” which I learned about from an interview with the author on the I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere podcast and then finished in two days.

Donovan’s book was quite interesting, if read a bit mechanically. Faye’s book is a great pastiche, interestingly written with both deep knowledge of the canon and a willingness to innovate, and very well read in this edition.

Over several weeks I have listened to the first half of “Anna Karenina” read by Maggie Gyllenhaal, which is superb. She brings a great saucy enthusiasm to the text and language, and it’s easy to imagine that one is being read to by her character from the film Secretary.

Finally, in the hope of better understanding American conservatism in order to better strategize about climate change, I have been listening to Geoffrey Kabaservice’s “Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, from Eisenhower to the Tea Party.” I’m still working through the 1960s, which is still fairly little-known history to me. The book is a bit challenging both because a lot of the names and events are unfamiliar and because the narrator is a bit monotone in a way that tends to enhance the difficulty of paying attention.

I found that such narration was commonplace in the books and spoken word content on Spotify, so generally I have been very happy about how Audible has shifted my listening toward fully accomplished published works with enduring social importance, rather than just the (sometimes excellent) present-focused podcast and news content.

Open thread: Urban thru hiking

Apparently it’s something that’s starting to exist:

Day hiking within city limits isn’t a new concept, of course. There are guidebooks detailing trails in cities from San Francisco to Atlanta. But Thomas has pushed the pursuit further, mapping out routes as long as 200 miles from one corner of a city to another and using infrastructure like stairways and public art to rack up elevation gain and provide something approximating a vista. She started in 2013 with a 220-mile through-hike in Los Angeles called the Inman 300, named for one of its creators, Bob Inman, and the initial number of stairways it included. Among other efforts, she has since hiked 60 miles through Chicago, 200 miles in Seattle, and 210 miles in Portland, Oregon. In 2015, she trekked the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on the 50th anniversary of that historic civil rights march.

The way I see it, urban thru hiking lets you walk more comfortably with less gear since you never need to make camp. Routes that amount to a serious sustained hike can be added up from segments which avoid car traffic as much as possible, and which link up with public transit to let you get home at the end of the day and back at the trailhead easily the next one.

Related:

Wooden insect art by Hermann Edler

Birds are beautiful

The 2021 Audubon Photography Awards feature some remarkable work. The video of a red tailed hawk soaring in the wind with its head uncannily unmoving is impressive, as doubtless is the dedication of all the people who took these shots.