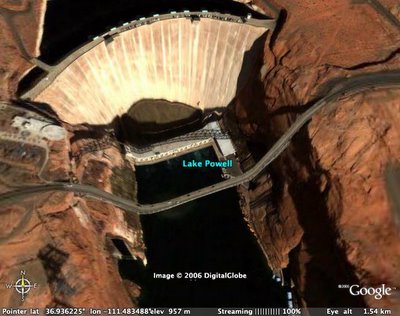

Normally, the Google Earth trick of taking altitude data from radar surveys and mapping aerial and satellite photographs on top has the neat effect of making the terrain look three dimensional. Sometimes, however, the radar map misses something and, when it draws the flat image onto the contoured terrain layer, you get a result like the one below:

Skip to content

climate change activist and science communicator; event photographer; amateur mapmaker — advocate for a stable global climate, reduced nuclear weapon risks, and safe human-AI interaction

Tristan took this photo from beside that dam.

Google Earth is an accidental Dali.

The shading and colouration make that look like a screenshot from Half Life 2.

For those who like Google Earth as much as I do, the Google Earth Blog bears examining.

The Glen Canyon Dam is also featured on Google Sightseeing: a site I recommend.

Lots of cool new Google Earth stuff from a Metafilter post.

One way to view the history of the American West is as a series of important moments in exploration or migration; another is to consider it, as Binney does, in terms of its water. In the 20th century, for example, all of our great dams and reservoirs were built — “heroic man-over-nature” achievements, in Binney’s words, that control floods, store water for droughts, generate vast amounts of hydroelectric power and enable agriculture to flourish in a region where the low annual rainfall otherwise makes it difficult. And in constructing projects like the Glen Canyon Dam — which backs up water to create Lake Powell, the vast reservoir in Arizona and Utah that feeds Lake Mead — the builders went beyond the needs of the moment. “They gave us about 40 to 50 years of excess capacity,” Binney says. “Now we’ve gotten to the end of that era.” At this point, every available gallon of the Colorado River has been appropriated by farmers, industries and municipalities. And yet, he pointed out, the region’s population is expected to keep booming. California’s Department of Finance recently predicted that there will be 60 million Californians by midcentury, up from 36 million today. “In Colorado, we’re sitting at a little under five million people now, on our way to eight million people,” Binney said. Western settlers, who apportioned the region’s water long ago, never could have foreseen the thirst of its cities. Nor, he said, could they have anticipated our environmental mandates to keep water “in stream” for the benefit of fish and wildlife, as well as for rafters and kayakers.