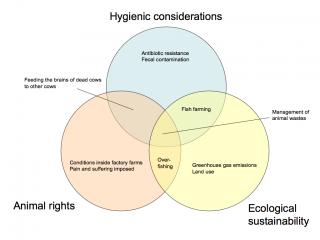

During the last few days, a number of people have asked about the reasons for which I am a vegetarian. As shown in the Venn diagram above, my reasons fall into three major clusters:

- Hygienic concerns

- Animal rights concerns

- Ecological concerns

Basically, the first category applies if you only think about your own immediate well being. If you are willing to consider the possibility that it is wrong to treat some animals in some ways, considerations in the orange circle start to apply. If you accept that we have general duties to preserve nature (or recognize that our long term survival depends on acting that way), issues in the yellow circle are of concern.

The specific issues listed are just examples. They are not exhaustive representations of all the problems in each area. Possible reasons for being vegetarian also exist outside these areas: for example, you can think it is wrong to eat meat when the grain used to fatten the animals could have alleviated the hunger of other humans.

A few issues are unambiguously in one area – for instance, the de-beaking of chickens is almost exclusively an ethical problem. The fact that no experimental laboratory could get ethical approval to treat their test subject animals in the way factory farmed animals are treated as a matter of course is telling. Some overlaps are ambiguous. Overfishing destroys the habitats of species I consider us to bear moral duties towards (such as whales and dolphins), even if the fish themselves can be legitimately used as means to whatever ends we have.

Naturally, different kinds of meat and processes of meat production do more or less well in each area. For my own sake, I think each of the three areas is sufficient in itself to justify vegetarianism. It is possible to imagine meat production that doesn’t have any of these problems, but it is an extreme rarity today and my appreciation for meat is not strong enough to justify the cost and effort of seeking it out. That said, I would be much happier if people who were going to consume meat made such choices, instead of helping to perpetuate the machinery of modern industrial farming.

Related prior posts:

“Humans — who enslave, castrate, experiment on, and fillet other animals — have had an understandable penchant for pretending animals do not feel pain. A sharp distinction between humans and ‘animals’ is essential if we are to bend them to our will, make them work for us, wear them, eat them — without any disquieting tinges of guilt or regret. It is unseemly of us, who often behave so unfeelingly toward other animals, to contend that only humans can suffer. The behavior of other animals renders such pretensions specious. They are just too much like us.”

Dr. Carl Sagan & Dr. Ann Druyan “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors” (1992)

Feeding the brains fo dead cows to other cows

Do people really do that?

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy

“A British inquiry into BSE concluded that the epidemic was caused by feeding cattle, who are normally herbivores, the remains of other cattle in the form of meat and bone meal (MBM), which caused the infectious agent to spread.”

“For many of the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease patients, direct evidence exists that they had consumed tainted beef, and this is assumed to be the mechanism by which all affected individuals contracted it. Disease incidence also appears to correlate with slaughtering practices that led to the mixture of nervous system tissue with hamburger and other beef. It is estimated that 400,000 cattle infected with BSE entered the human food chain in the 1980s. Although the BSE epizootic was eventually brought under control by culling all suspect cattle populations, people are still being diagnosed with vCJD each year (though the number of new cases currently has dropped to less than 5 per year). This is attributed to the long incubation period for prion diseases, which are typically measured in years or decades. As a result the full extent of the human vCJD outbreak is still not fully known.”

It seems they feed cows non-brain parts of other cows, but allow some cow-brain-parts into the human food supply.

Why organic and free range?

“The short answer is that organic meat and dairy products will likely be better for your health than non-organic ones. Free range eggs similarly, plus there is an animal rights factor.”

The Meatrix

“Take the red pill and watch the critically-acclaimed, award-winning first episode of The Meatrix Trilogy.”

Canada confirms new case of mad cow disease

Tue Dec 18, 2007 11:43am EST

OTTAWA (Reuters) – Canada confirmed a new case of mad cow disease on Tuesday, the 11th since 2003, and said the animal in question was a 13-year-old beef cow from Alberta.

Yo Milan,

In terms of “Feeding the brains fo dead cows to other cows”, it would be more accurate to say that it used to happen but doesn’t anymore.

I would refer you to:

link

As the CFIA says, the specified risk material shouldn’t be going into the human (or animal) food chain.

Rest assured, only crazed Night-of-the-Living-Dead-Bovine zombie cows are eating the brains of other cows nowadays in Canada. And bovine versions of Bruce Campbell are dealing with that particular problem.

(A note aside, I’m not sure there actually have been any conclusive studies showing a definite link between consumption of BSE-infected material by humans and CJD.)

In terms of the other sections of your Venn diagrams, I would like to point out that many of these concerns could also be addressed by purchasing as an enlightened consumer and by eating animal products in moderation. You can certainly buy organic meat as well as organic veggies, if you so choose.

Farming practices, including fish farms (as noted by the author of that recent study criticizing some BC fish farms), when done in the proper method need not be environmentally detrimental. Regarding fecal contamination, it can be eliminated if the proper practices in either meat or vegetable production, organic or otherwise are followed.

Re:

“The short answer is that organic meat and dairy products will likely be better for your health than non-organic ones. Free range eggs similarly, plus there is an animal rights factor.”

– and as befitting a short answer, is short on evidence and kinda long on advice in what is very definitely a very nuanced subject with a non-black or white answer. The organic food cabal can be just as suspect at making sketchy blanket claims as the Monsanto posse can. Responsible use of pesticides and herbicides should pose no threat to human health.

In terms of animal welfare, you can be a meat consumer and still see the ethical treatment of farm animals in a non-organic setting. Research into the economic benefits of having contented animals can be seen at UBC’s own:

link

Seriously, going veggie is definitely one way to address the concerns in your Venn diagrams, but I don’t think its false to say can address these same problems by being a smart consumer and supporting producers who farm in an ethical and sustainable way, organic or otherwise.

HUMOUR FOLLOWS

Re: flatulant farm critters

I think Buffalo Bill merits some revisionist consideration for his forward-thinking policy of large scale herbivore population culls… He may have bought the planet’s atmosphere precious YEARS with his methane-reduction. (insert Triumph the Insult Dog, “I kid, I kid” here, ha ha)

This is a very clear and communicative way of expressing the fact that there are many different but relating reasons to remove oneself from the sphere of meat eating.

The real difference for me concerns this statement:

“It is possible to imagine meat production that doesn’t have any of these problems, but it is an extreme rarity today and my appreciation for meat is not strong enough to justify the cost and effort of seeking it out.”

I’m having trouble with this. On the one hand I want to say it isn’t up to individuals to make these kind of universal choices, that they have the right to act particularly, on their own interests. And, since eating meat is a significant part of human history and culture, they have a significant interest in participating in that aspect of humanity by eating meat. However, it seems wrong to say humans have the moral right to act in a particular and selfish manner. Maybe what I want to say is that humans don’t need to act rightly all the time. The right action is alienating, and often contradicts the compassionate aspect of a situation (as in the victim of an invasive crime, who has the moral duty to report it, but asking them to report it might violate every compassionate bone in one’s body).

I don’t want to have to become vegetarian again.

How do the arguments above not require you to be a vegan? All three sets of criticisms apply just as much to the cows and chickens kept alive for intensive milk and egg production.

Another nice graphic, which is a notable skill of yours Milan.

Alas, people very often work backwards from what they currently think or do until they achieve a set of reasons and arguments that justify it, rather than altering their beliefs and actions to fit an ethical or logical framework that they would suppport. This means that “I don’t want to become a vegetarian again” can be a tempting reason to construct arguments against animal rights, or to disregard evidence on sustainability.

While it seems reasonable enough to me that one could choose not to worry about hygienic concerns vis-a-vis meat consumption (since this is an individual cost or benefit), I’m not convinced people have the right to set aside considerations of animal rights or sustainability even if they feel ‘alienated’ by the right course of action. Saying that something is a historical practice or that it is an integral part of one’s culture is a poor ethical justification, especially that humans have regularly done barbaric things to one another (and to the environment & animals) for reasons of habit and self-interest: the American Civil War provides a pretty good example of a practice deemed essential by one group of people and morally repugnant by others employing better reasoning. At minimum, historial precedent and/or cultural norms might be considered a very minor ethical consideration – enough to sway the balance if no great harms or goods were involved. Given the sustainability concerns around meat production (especially, I hear, beef) I think anyone who intends to act ethically has to either deliberately limit their CO2 production, offset their consumption in an effective manner elsewhere (where ‘effective’ does not equal giving money to cowboys who provide minimal additionality), or demonstrate that the several other ‘Earths’ required to support such resource-intensive behaviour are ready & available for pillaging.

One more thing:

Even if the statement on the graphic was “feeding the remains of cows in the form of meat and bone meal (MBM) to other cows” it would qualify as unethical and gross, and nobody is disputing that that occurs. The arguments above are about which bits of cows are fed cannibalistically to their soon-to-be-slaughtered peers, not about whether such forced cannibalism is taking place.

A more meaningful criticism of these “ethical” arguments against meat eating, or at least most meat eating, would be to question the ethics of non-violence its grounded upon. I would say that supposing violence is wrong and the right thing to do is to avoid doing violence doesn’t give you an ethics or morality at all. What the moral law needs to do is to tell us how to act, not how not to act. In other words, it needs to be grounded on a positive not a negative duty.

And, I don’t see in what way a theory of moral action could be given in terms of non-violence. Certainly it might end up that it can be described as non-violent, but since all assertions of the will violate something, there is a slippery slope problem as to what is allowed to be violated and what is not. The solution it seems is to begin from the other side: How to act, rather than how not to act. This would work towards a theory of righteous violence.

Of course such things have been used to justify atrocities, but what is the alternative but limp wristed rehashed christian slave morality?

Farming practices, including fish farms (as noted by the author of that recent study criticizing some BC fish farms), when done in the proper method need not be environmentally detrimental.

I don’t think fish farming can ever be environmentally sustainable if the fish being farmed are carnivores. If we had the self-restraint not to fish whatever we are feeding them into extinction, we would be better off exercising the same restraint in relation to wild stocks of the fish we actually eat.

Fish farming simply delays the inevitable, while creating many problems of its own.

A more meaningful criticism of these “ethical”… …limp wristed rehashed christian slave morality?

Tristan,

Can you please explain all that using language other people reading will understand? It is pretty frustrating to be spoken to using incomprehensible terminology, and it discourages people from engaging in the discussion.

In terms of “Feeding the brains fo dead cows to other cows”, it would be more accurate to say that it used to happen but doesn’t anymore.

Maybe not brains, but other body parts. Doesn’t that strike people as a kind of affront to nature? It is dangerous to base moral arguments on gut reactions, but turning herbivores into cannibals strikes me as a bit like desecrating a corpse: even if you don’t think we owe any moral duties to corpses (or animals), it can be morally wrong to treat them in ways that demonstrate profound disrespect.

many of these concerns could also be addressed by purchasing as an enlightened consumer and by eating animal products in moderation. You can certainly buy organic meat as well as organic veggies, if you so choose.

The argument for eating less meat seems both very strong and very weak. If we accept that eating meat is wrong, eating less of it is less wrong. At the same time, it is still wrong.

The argument that some meat doesn’t have these negative properties, I accept. I just don’t find it personally worth the bother to locate an ethical farm, get out there in a sustainable way, buy meat, and prepare it myself.

Farming practices, including fish farms (as noted by the author of that recent study criticizing some BC fish farms), when done in the proper method need not be environmentally detrimental.

This is a tautology, since “proper method” implies “not environmentally detrimental.” I accept that farming can be done sustainable. Fish farming I have serious doubts about.

Responsible use of pesticides and herbicides should pose no threat to human health.

Potentially true, though human health is not the only concern. The fact that pesticides kill birds and fertilizers cause the eutrophication of rivers are not irrelevant. There is more wrong with non-organic farming than threats to humans from the poisons employed.

I don’t think its false to say can address these same problems by being a smart consumer and supporting producers who farm in an ethical and sustainable way, organic or otherwise.

It is possible to be an ethical meat consumer, but it is extremely difficult if you are concerned about all three areas of that Venn diagram. Between animal rights concerns, ecological sustainability (including induced deforestation), and hygienic concerns there is virtually no meat in the world that is ethically acceptable. Finding it would take a lot of personal effort.

Incidentally, I consider fish to be meat, by definition.

And, since eating meat is a significant part of human history and culture, they have a significant interest in participating in that aspect of humanity by eating meat.

Selling daughters played “a significant part of human history and culture.” This is no argument for eating meat. It is just an argument for the perpetuation of the status quo, in the absence of moral reflection.

Maybe what I want to say is that humans don’t need to act rightly all the time.

They almost certainly cannot achieve such a high standard, but that doesn’t excuse people from being as ethical as they possibly can be, given their knowledge and resources.

I don’t want to have to become vegetarian again.

I don’t want to become vegan, but I can see little reason for not doing so. That said, the sheer inconvenience of it really puts me off (and I love cheese).

Sarah,

Alas, people very often work backwards from what they currently think or do until they achieve a set of reasons and arguments that justify it, rather than altering their beliefs and actions to fit an ethical or logical framework that they would suppport.

This is true. See my comment about veganism in the comment above this one.

Saying that something is a historical practice or that it is an integral part of one’s culture is a poor ethical justification, especially that humans have regularly done barbaric things to one another (and to the environment & animals) for reasons of habit and self-interest

I agree completely. There is nothing sacred in tradition.

Given the sustainability concerns around meat production (especially, I hear, beef) I think anyone who intends to act ethically has to either deliberately limit their CO2 production, offset their consumption in an effective manner elsewhere (where ‘effective’ does not equal giving money to cowboys who provide minimal additionality), or demonstrate that the several other ‘Earths’ required to support such resource-intensive behaviour are ready & available for pillaging.

I agree that there is intuitive appeal to the “here is your fair slice of the Earth, do with it as you will” approach. That said, it only really covers the ecological sustainability portion of the diagram. Furthermore, it can be convincingly argued that virtually everyone living in the West is already taking more than their fair share: at the cost of people elsewhere and future generations.

Litty,

How do the arguments above not require you to be a vegan?

Logically, they do require me to be vegan. Dairy cows are fed the same garbage, they live equally miserable lives, and factory meat and egg production is ecologically unsustainable.

Here is where I can only really fall back on the ‘eating less is better’ argument. I virtually never buy milk and rarely buy eggs. When I buy the latter, I try to buy the most ethical ones available. Cheese I personally love. As such, I can only consider it as part of my intentionally chosen ecological footprint.

When it comes to the misery of the dairy cows, I have no defence.

The arguments above are about which bits of cows are fed cannibalistically to their soon-to-be-slaughtered peers, not about whether such forced cannibalism is taking place.

True enough. This comment inspired my reference above to the desecration of nature. Even if we don’t accord meaningful rights to an entity, we can consider it wrong to deface or despoil it. A statue has no rights, neither does a towering Redwood. That said, a case can be made that it is wrong to destroy either, even if nobody mourns the loss.

That feeling is hard to square with my general utilitarian framework. The circle can be squared in a clumsy way by saying: “We prefer to live in a world in things are not despoiled,” but that isn’t a very sophisticated or convincing argument.

The whole point of these discussions is to refine our ideas.

I don’t think fish farming can ever be environmentally sustainable if the fish being farmed are carnivores. If we had the self-restraint not to fish whatever we are feeding them into extinction, we would be better off exercising the same restraint in relation to wild stocks of the fish we actually eat.

This is not necessarily true. Think about successive levels of the food web and levels of energy (all imaginary example numbers):

Phytoplankton (100%)

Zooplankton (80%)

Tiny fish (50%)

Middle sized fish (30%)

Big fish (10%)

It is possible that by catching and grinding up the middle sized fish and feeding them to the big fish in the right conditions, we can actually get more big fish than nature would allow.

That said, I agree that all existing commercial fish farming is probably ecologically unsustainable. It is a classical tragedy of the commons problem. The fish farmer doesn’t care whether there will be any middle sized fish in fifty years – at least, they don’t care enough to stop exploiting them.

I still disagree that morality grounded on this kind of non-violence doesn’t produce a theory of action; it produces a theory of inaction. It says “don’t act if your actions violate the sovereignty of another moral being”. But all actions do that, to some extent or another. So you have to draw a line, and then morality is contingent on how well you can defend some arbitrary line against the slippery slope case.

I would suggest as an alternative morality as the theory of how do you make your actions such that they make actual something which isn’t merely arbitrary. For example, whether I like ice cream or not is arbitrary; it could have been otherwise. On the other hand, if there is some moral imperative, while you can either act on it or not act on it (that is the condition for it being voluntary), following it doesn’t seem arbitrary at all. Would you want to say its just random whether or not you “did the right thing”, or even that its causally determined in the same way as the biological explanation for liking or not liking ice cream?

Our Decrepit Food Factories

By: Michael Pollan

The word “sustainability” has gotten such a workout lately that the whole concept is in danger of floating away on a sea of inoffensiveness. Everybody, it seems, is for it whatever “it” means. On a recent visit to a land-grant university’s spanking-new sustainability institute, I asked my host how many of the school’s faculty members were involved. She beamed: When letters went out asking who on campus was doing research that might fit under that rubric, virtually everyone replied in the affirmative. What a nice surprise, she suggested. But really, what soul working in agricultural science today (or for that matter in any other field of endeavor) would stand up and be counted as against sustainability? When pesticide makers and genetic engineers cloak themselves in the term, you have to wonder if we haven’t succeeded in defining sustainability down, to paraphrase the late Senator Moynihan, and if it will soon possess all the conceptual force of a word like “natural” or “green” or “nice.”

“To call a practice or system unsustainable is not just to lodge an objection based on aesthetics, say, or fairness or some ideal of environmental rectitude. What it means is that the practice or process can’t go on indefinitely because it is destroying the very conditions on which it depends. It means that, as the Marxists used to say, there are internal contradictions that sooner or later will lead to a breakdown.”

“This is a tautology, since “proper method” implies “not environmentally detrimental.” I accept that farming can be done sustainable. Fish farming I have serious doubts about.”

Nuts to your tautology reference Milan, that’s so high school debate club. Don’t be a Kevin Massey. You know what I was trying to say (next time I swear I’ll run the MS Word Tautology checker, just for you). Fish farming can be environmentally sustainable.

I don’t disagree that many current farms, be they fish, meat, field crops, etc., have problems. However, I think some people forget that farming technology and practices aren’t static. As with any production method, practices improve with research and direct experience. Farmers and regulators can and do change methods over time.

I think that while increasing yield has been one of the driving forces of change in agriculture historically, sustainability is now definitely one of the main currents of research and change.

And you can “tragedy of the commons” me all you want. That’s why we have government regulation, inspectors and consumers with access to information. Ayn Rand wrote fiction! Remember that!

“Logically, they do require me to be vegan. Dairy cows are fed the same garbage, they live equally miserable lives, and factory meat and egg production is ecologically unsustainable.”

Milan, words almost fail me. How are you supposed to argue with a blanket statement like that loaded with generalizations? Heck, a lot of non-animal product farms have ecological and ethical implications, too. Draining aquifers, unsafe chemical use, clearing of forests, carbon footprints, distance-to-consumer, etc., etc. I don’t think what you’re arguing for is to be vegan necessarily but rather better regulation of all types of farming.

@Not Gurstein

“Milan, words almost fail me. How are you supposed to argue with a blanket statement like that loaded with generalizations?”

Fair enough. Are there specific reasons for which dairy farms are more ethical, hygienic, and sustainable?

“Heck, a lot of non-animal product farms have ecological and ethical implications, too.”

True, but they are more sustainable than meat farms. We do need to be concerned about other ecological problems relating to farming, like fertilizer runoff. At the same time, it seems that we basically agree that it is ethically superior to be a vegetarian and probably better still to be a vegan. A reasonable case can be made that it is inethical not to be, given the range of choices open to us as individuals.

Is it possible to live ethically in our society?

“Heck, a lot of non-animal product farms have ecological and ethical implications, too. Draining aquifers, unsafe chemical use, clearing of forests, carbon footprints, distance-to-consumer, etc., etc. I don’t think what you’re arguing for is to be vegan necessarily but rather better regulation of all types of farming.”

Hmm, lots of violence in vegetable farms. I guess I’d better not eat at all.

Oh wait, I’ve turned into Saint Simon the pole sitter.

I never used the word “more” in relation to dairy. My point was that all forms of farming can be ethical, sustainable and hygienic.

Dairy farming does not necessarily result in “miserable” cows eating “garbage”. From a Canadian farm sector perspective, I find using those words highly questionable.

I’m not sure I agree that it is ethically superior to be a vegetarian, etc., because my point was that it is possible to be an ecologically and ethically responsible consumer of animal products. Neither way is superior as long as you buy responsibly.

@Tristan

http://www.detnews.com/2005/business/0502/21/business-94529.htm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4513874.stm

Just saying that no matter what form of farming, there can always be ethical and ecological problems, and yes, even violence.

I’d source my soy burger if I were you.

There is an ambiguity here. Is this post a listing of the reasons for which Milan specifically is a vegetarian? Or is it an argument for why all people ought to be?

In the first place, this seems like a convincing and well-argued justification for a personal choice.

In the second, it seems like the arguments in the comments show that it is possible to eat meat without causing the problems that concern Milan.

One notable feature of this discussion is that nobody has defended ‘ordinary’ meat. Organic and free range stuff might be acceptable, but there seems to be unanimous agreement that standard restaurant or supermarket meat is unacceptable. Do non-vegetarians who agree with this ever eat meat at restaurants or the houses of friends with fewer ethical qualms?

Selling daughters played “a significant part of human history and culture.”

Stephanie Sinclair won the UNICEF photo of the year for her haunting picture of a 40-year-man and his 11-year-old bride in Afghanistan.

He’s forty, she’s eleven. And they are a couple – the Afghan man Mohammed F.* and the child Ghulam H.*. “We needed the money”, Ghulam’s parents said…

They predict that Ghulam will be married within a few weeks after her engagement in 2006, so as to bear children for Faiz.

I’m always amazed by what short-term historical memories my peers have. Organic and free-range farming are viewed as the latest Vancouverite snob trent, and factory farmed meat is considered “ordinary”.

It is not normal or historically common to raise meat in industrialized settings. I am not a farmer so I can only speculate on whether or not there are some types/techologies in factory farming that can be less detrimental to the environment than free range or herd farming. However, it is not an overgeneralization to say that the current state of ‘ordinary’ meat production and consumption are unsustainable due to the wasteful use of water and grain, and the high run-off from the “Bovine Universities”. Consumption is also a big issue-I imagine that even if we free-range farmed all our beef but kept consuming it at the same rate, overgrazing would soon be a problem.

In many West African countries, goats and chickens are raised by scavenging for food that humans can’t eat. It is possible for many towns to raise goats and chickens without overgrazing the land, or using wasteful feeding methods. The taste? Uh…well you get used to it.

Kerrie,

I both agree and disagree. Factory farmed meat is not ‘normal’ historically. It has only really existed for a handful of decades.

At the same time, it is probable that a majority of readers on this blog have eaten nothing else – barring the occasional bug in childhood.

An ‘ordinary’ car isn’t ordinary, when you consider the sweep of history, but it is certainly ordinary to a 25-year-old today.

Granted, most of us are accustomed to it. But it seems really strange to be making arguments about what a society should do without thoughtfully considering the past and future.

I mean hell, I sympathise, I don’t even remember what life was like before I turned 18 and got the internet! Nevertheless!

That the biggest grain harvest the world has ever seen is not enough to forestall scarcity prices tells you that something fundamental is affecting the world’s demand for cereals.

Two things, in fact. One is increasing wealth in China and India. This is stoking demand for meat in those countries, in turn boosting the demand for cereals to feed to animals. The use of grains for bread, tortillas and chapattis is linked to the growth of the world’s population. It has been flat for decades, reflecting the slowing of population growth. But demand for meat is tied to economic growth and global GDP is now in its fifth successive year of expansion at a rate of 4%-plus.

Higher incomes in India and China have made hundreds of millions of people rich enough to afford meat and other foods. In 1985 the average Chinese consumer ate 20kg (44lb) of meat a year; now he eats more than 50kg. China’s appetite for meat may be nearing satiation, but other countries are following behind: in developing countries as a whole, consumption of cereals has been flat since 1980, but demand for meat has doubled.

Not surprisingly, farmers are switching, too: they now feed about 200m-250m more tonnes of grain to their animals than they did 20 years ago. That increase alone accounts for a significant share of the world’s total cereals crop. Calorie for calorie, you need more grain if you eat it transformed into meat than if you eat it as bread: it takes three kilograms of cereals to produce a kilo of pork, eight for a kilo of beef. So a shift in diet is multiplied many times over in the grain markets. Since the late 1980s an inexorable annual increase of 1-2% in the demand for feedgrains has ratcheted up the overall demand for cereals and pushed up prices.

“Give a man a fish and you have fed him for a day. Give a man a seafood choice card and you have made him impossible to dine with.”

September 10th, 2005

“I decided, less than a week ago, to stop eating factory farmed meat. The reasons are threefold. In short, it is unsustainable as well as ethically and hygienically repulsive. The newest theory about the emergence of BSE (see Alan Colchester in The Lancet) powerfully underscores the third point.”

“Prion” is derived from Proteinaceous infectious particle

Eat less meat to fight climate change, IPCC chief says

By Bill Miller on Organizations

Rajendra Pachauri an Indian economist and a vegetarian, said the 2007 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlights “the importance of lifestyle changes,” and the need for people around the world to curb their carnivorous appetites.

Studies have shown producing 2.2 pounds of meat causes the emissions equivalent of 80 pounds of carbon dioxide, Pachauri told a press conference. In addition, raising and transporting that slab of beef, lamb or pork requires the same energy as lighting a 100-watt bulb for three weeks.

“Please eat less meat,” he said, “meat is a very carbon intensive commodity.”

He also advocated cycling or walking “instead of jumping in a car to go 500 metres,” and urged consumers to purchase only what they really need instead of buying something “just because it’s there.”

Then there are the dreaded V-words: vegetarian and vegan. Few politicians or environmentalists want to face the jokes, media backlash and libertarian “consumer freedom” zealots who will accuse them of forcing Canadians to eat only salad and lentils. The same sort of people who fought against mandatory seatbelts and restrictions on tobacco would shift their public relations and spin machines into high gear.

Yet all the IPCC is asking for is a reduction in meat consumption. A recent study in the prestigious medical journal The Lancet called for a 10-per-cent cut in meat consumption, which it said would slow global warming considerably. It would also slow the growth of factory farming, which is alarming animal welfarists around the world. Global demand for meat is projected to double between 2001 and 2050%2

Rethinking the Meat-Guzzler

A SEA change in the consumption of a resource that Americans take for granted may be in store — something cheap, plentiful, widely enjoyed and a part of daily life. And it isn’t oil.

It’s meat.

The two commodities share a great deal: Like oil, meat is subsidized by the federal government. Like oil, meat is subject to accelerating demand as nations become wealthier, and this, in turn, sends prices higher. Finally — like oil — meat is something people are encouraged to consume less of, as the toll exacted by industrial production increases, and becomes increasingly visible.

For the record, I’m con bestiality (and very much pro cunnilingus). I think fucking dogs is wrong, wrong, wrong. But I had pork and beef and chicken at dinner last night—all 100 percent factory-farmed meat, derived from animals that were cruelly tortured every second of their brief and miserable existence—and my particular strain of Tourette’s syndrome commands me to say this: If I were an animal, I’d much rather be screwed than stewed. We murder animals for their flesh, skins, fur, and just for the fuck of it. Those of us that eat meat; wear fur; run around in leather pants, jackets, shoes, restraints, etc.; and kill animals for sport don’t have much moral authority when it comes time to lecture those of you who wanna smooch the pooch.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization expects that global meat production will double by 2050 – growing, in other words, at two and a half times the rate of human numbers. The supply of meat has already trebled since 1980: farm animals now take up 70 percent of all agricultural land and eat one third of the world’s grain. In the rich nations we consume three times as much meat and four times as much milk per capita as the people of the poor world. While human population growth is one of the factors that could contribute to a global food deficit, it is not the most urgent.

I Love You, but You Love Meat

SOME relationships run aground on the perilous shoals of money, sex or religion. When Shauna James’s new romance hit the rocks, the culprit was wheat.

“I went out with one guy who said I seemed really great but he liked bread too much to date me,” said Ms. James, 41, a writer in Seattle who cannot eat gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley and rye.

Sharing meals has always been an important courtship ritual and a metaphor for love. But in an age when many people define themselves by what they will eat and what they won’t, dietary differences can put a strain on a romantic relationship. The culinary camps have become so balkanized that some factions consider interdietary dating taboo.

Hezbollah Tofu

A Bourdain-Veganizing Collective

The Simpsons – Lisa the Vegetarian

Vegetarianism and environmentalism

On PETA’s latest campaign

Should citizens of conscience become vegetarians?

To me, the answer to this question is pretty obviously yes. I don’t see how it can be seriously argued.

Meatless Like MeI may be a vegetarian, but I still love the smell of bacon

By Taylor Clark

Posted Wednesday, May 7, 2008, at 11:51 AM ET

I tell this story not to win your pity but to illustrate a point: I’ve been vegetarian for a decade, and when it comes up, I still get a look of confused horror that says, “But you seemed so … normal.” The U.S. boasts more than 10 million herbivores today, yet most Americans assume that every last one is a loopy, self-satisfied health fanatic, hellbent on draining all the joy out of life. Those of us who want to avoid the social nightmare have to hide our vegetarianism like an Oxycontin addiction, because admit it, omnivores: You know nothing about us. Do we eat fish? Will we panic if confronted with a hamburger? Are we dying of malnutrition? You have no clue. So read on, my flesh-eating friends—I believe it’s high time we cleared a few things up.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/7600005.stm

Have fries with that — or just the fries

Beef has 13 times more climate impact than chicken, 57 times more than potatoes

Posted by Joseph Romm (Guest Contributor) at 11:29 PM on 28 Jan 2009

This is brilliant – and what an amazing core of readers you have. I have problems with dairy, too. I don’t eat any cow products, but I do indulge in goat cheese (organic only). I also eat eggs, but choose organic, free range. I occasionally make exceptions when I’m in a restaurant or at someone’s home. I don’t think it pays to be too fanatical and making few exceptions now and again doesn’t rule out all the good otherwise.

Agreed.

One of my tastiest exceptions: Delicious pike

The Kindest Cut

Which meat harms our planet the least?

By Nina Shen Rastogi

Posted Tuesday, April 28, 2009, at 6:54 AM ET

Green Lantern, you’re always telling us how bad meat is for the environment. I’m willing to throw some more zucchini kebabs on my barbecue this summer, but are all meats equally awful? Or are there some that I can grill with a little less guilt?

…

As a general rule, red meat—beef, lamb, goat, and bison—are the worst offenders.

…

Poultry and eggs come out best of all. Chickens breed furiously—a single bird can produce hundreds of chicks annually—and are highly efficient weight gainers. A recent independent life cycle analysis on U.S. poultry found that producing a calorie of chicken protein required about 5.6 calories of fossil fuels, compared with reported figures of about 14 calories for pork and 20 to 40 for beef. Still, as the most widely eaten meat in America, chicken farming has a major impact on the environment. The poultry-broiler industry consumed some 240 billion megajoules of energy in 2005, or the equivalent of 42 million barrels of crude oil. That’s more than the entire country of Sri Lanka consumed the same year—all to keep us well-stocked with wings and drumsticks.

Livestock main source of E. coli: study

DNA fingerprinting shows human sewage only a tiny fraction of the problem

By Tom Spears, The Ottawa CitizenMay 5, 2009

Manure from cattle and pigs far outweighs human sewage as the source of E. coli pollution in Lake Huron, says a new Canadian study that helps show why the bacteria pollution problem is growing.

After years of arguments over where the disease-carrying bacteria come from — humans, livestock or wildlife — DNA “fingerprinting” says human sewage is only a tiny fraction of the problem.

In samples from Lake Huron and the creeks and rivers feeding it, cattle and pig manure accounted for 59 to 62 per cent of the E. coli.

Human sewage contributed just one to three per cent. The rest came from wildlife, from bacteria that have adapted to living in the water, or from sources that couldn’t be identified.

Meat Guilt

Posted on: June 3, 2009 2:29 PM, by Jennifer L. Jacquet

A blogpost over at GOOD magazine* reviews a new book on veganism, applauds the book for its flexible approach, and says we should “give up trying to guilt people into not eating any meat.” The post mentions the environmental impacts of meat, which are indeed significant (according the the UN, rearing cattle produces more greenhouse gases than driving cars), but does not venture much further in the realm of why there is a guilt campaign around meat eating (which, I would argue, has been a fairly weak campaign — the potential for gruesomeness hardly fulfilled at all).

If it is not yet clear on this platform, I question the use of guilt as an effective medium for change, too. However, I believe there are plenty of reasons to feel guilty about the prolific meat eating by North American consumers (and some European ones) and that this guilt is justified and, if anything, understated. Anyone unfamiliar with the obscenely inhumane practices of raising meat in this country should try Google or at least read The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan (a flexitarian himself, with perfectly reasonable views on how to approach one’s diet: Eat food. Mostly plants. Not too much. As for the meat we eat, we should know how its raised and ensure that’s it’s raised in the most humane conditions possible). It’s not particularly noble or brave to downplay just how foul the meat industry is and how guilty and ashamed we should all feel for allowing it to persist and overproduce.

Is There Really a Debate over Seafood?

Category: Food Systems • Guilt

Posted on: June 11, 2009 1:07 PM, by Jennifer L. Jacquet

Whether we should continue eating seafood is a hot topic this week. While I was arguing (again) that we should give up eating seafood, Mark Bittman at the New York Times had a nice piece on how seafood has changed through his lifetime and how the days of “see it/eat it” are over. However, he stops short of a strong stance and tries to justify his continued seafood consumption:

“One could argue, as I sometimes do (mostly to myself), that one shouldn’t eat fish at all, fearing that if fish lovers begin consuming those few remaining species that are not in trouble — sardines, mackerel, squid — we might just make quick work of them, too. But though that may be the easiest argument to phrase, it isn’t likely to be popular, nor will it help the cods and flounders.”

Similarly, the debate (which is not particularly compelling since no one argued we should stop eating seafood altogether–again, fish need a wide spectrum of voices) rages on at the NYTimes blog.

Here’s the thing: if you do choose to eat eggs, despite the captivity of the birds, you should be buying eggs from small egg operations. These operations should have freely ranging chickens, and may have roosters. Hence, if you are going to eat eggs, it is better to buy and eat the ones that extremely hypothetically might have resulted in a live chick. Large-scale chicken egg farming is economically, ethically, and environmentally repugnant.

Mildly,

Umbra

“For every newly converted vegetarian, four poor humans start earning enough money to put beef on the table. In the past three decades, the earth’s dominant carnivores have tripled our average per capita consumption; in the next four decades global meat production will double to 465 million tons.”

This video is a good demonstration of why vegetarianism might not be enough. If we care about animal welfare (and the harmful consequences of factory farming), we might be morally obligated to go vegan.

Beware the Myth of Grass-Fed Beef

Cows raised at pasture are not immune to deadly E. coli bacteria.

By James E. McWilliams

Posted Friday, Jan. 22, 2010, at 7:24 AM ET

On Monday, Huntington Meat Packing Inc. recalled a whopping 864,000 pounds of beef thought to contain a particularly nasty strain of E. coli bacteria called O157:H7. Coming shortly after the recall of 248,000 pounds of beef by National Steak and Poultry on Christmas Eve—and dozens of other scares over contaminated beef and pork—this latest news reminds consumers yet again that the mass production of meat can be very dangerous indeed.

Consumers who still have an appetite for burgers and sirloins have been pushed toward alternative food sources. In particular, they’ve started to seek out more wholesome meat from animals raised in accordance with their natural inclinations and heritage. According to Patricia Whisnant, president of the American Grassfed Association, there’s been a dramatic rise in demand for cattle reared on a pasture diet instead of an industrial feed lot. Grass-fed beef should account for 10 percent of America’s beef consumption overall by 2016, she says—a more than threefold increase from 2006.

The comparative health benefits of grass-fed beef are well documented. Scores of studies indicate that it’s higher in omega 3s and lower in saturated fat. But when it comes to E. coli O157:H7, the advantages of grass-fed beef are not so clear. In fact, exploring the connection between grass-fed beef and these dangerous bacteria offers a disturbing lesson in how culinary wisdom becomes foodie dogma and how foodie dogma can turn into a recipe for disaster.

This article features a nice graphic showing how the relative quantity of federal subsidies for different kinds of food differs from nutritional recommendations.

Meat and dairy get over 73% of the subsidies, but are the second smallest recommended category for consumption. The second largest category recommended (grains) gets about 13% of subsidies. Fruits and vegetables apparently get less than 0.5% of subsidies.

It is worth noting that these nutritional recommendations already reflect the fact that government bureaucracies are in the pocket of the farm lobby.

Consider the Oyster

Why even strict vegans should feel comfortable eating oysters by the boatload.

By Christopher Cox

Posted Wednesday, April 7, 2010, at 6:55 AM ET

There are dozens of reasons to become a vegan, but just two should suffice: Raising animals for food 1) destroys the planet and 2) causes those animals to suffer. Factory farms are the worst offenders, but even the best-run animal operations can’t get around the fact that livestock are the largest contributors to global warming worldwide and that the same amount of land used to feed one beef-eater can feed 15 to 20 vegans. Animals are terribly inefficient machines for turning plants into food, and an inefficiency of this scale is disastrous. The animal welfare argument is even simpler: While there are limitless ways in which humans are different from nonhuman animals, one thing we share with most is the ability to feel pain. Since I consider it unethical to cause you, dear reader, undue pain, there’s no reason—other than simple preference for my own species—to have a separate standard for mammals, fish, and birds.

But what if we could find an animal that thrived in a factory-farm cage, one that subsisted on nutrients plucked from the air and that was insensate to the slaughterhouse blade? Even if that animal looked like a bunny rabbit crossed with a puppy, it would be A-OK to hack it into pieces for your dinner plate. Luckily for those of us who still haven’t gotten over the death of Bambi’s mother, the creature I’m thinking of is decidedly less cuddly. Biologically, oysters are not in the plant kingdom, but when it comes to ethical eating, they are almost indistinguishable from plants. Oyster farms account for 95 percent of all oyster consumption and have a minimal negative impact on their ecosystems; there are even nonprofit projects devoted to cultivating oysters as a way to improve water quality. Since so many oysters are farmed, there’s little danger of overfishing. No forests are cleared for oysters, no fertilizer is needed, and no grain goes to waste to feed them—they have a diet of plankton, which is about as close to the bottom of the food chain as you can get. Oyster cultivation also avoids many of the negative side effects of plant agriculture: There are no bees needed to pollinate oysters, no pesticides required to kill off other insects, and for the most part, oyster farms operate without the collateral damage of accidentally killing other animals during harvesting. (Relatedly, although it’s possible to collect wild oysters sustainably, the same cannot be said for other bivalves like clams and mussels. These are often dredged from the seabed, disrupting an entire ecosystem. For that reason, it’s best to avoid them.)

Here is a discussion on the ethics of Canada’s seal hunt.

“How violent is a rancher or dairy farmer allowed to get with his livestock?

In some states, as violent as he likes. Farmers, for the most part, are merely expected to abide by industry standards—that is, to treat their livestock as other farmers do. Lifelong confinement in small cages and using a hot blade to trim a chicken’s beak, for example, are widely permitted as customary agricultural practices. (A handful of states, however, have recently prohibited certain confinement systems.) Acts of violence or mutilation are typically illegal only if they are unnecessary and out of the ordinary. Because stomping on a calf’s head is hardly a tradition in animal husbandry, Ohio prosecutors could try to press charges, but at worst the dairy farmers will get slapped with misdemeanors. To face a felony charge for animal cruelty in Ohio, the perpetrator has to abuse a companion, laboratory, or zoo animal.

Federal law has very little to say about the treatment of livestock. The Animal Welfare Act applies mainly to research animals. The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act requires farmers to knock out livestock with a single blow, shot, or electrical charge before being butchering them, but the law only governs slaughterhouses, not farms. (It also doesn’t apply to poultry, which represents more than 95 percent of slaughtered animals. You’re free to kill your chicken any way you like under federal law.) The 28 Hour Law of 1873 requires that farm animals get five hours of R & R for every 28 hours of train transport, but few cattle ride the rails these days.”

Sheep prove less than woolly-headed after all

Daily Telegraph

Published: Sunday, February 20

Their apparent dim-wittedness has made sheep a byword for stupidity and mindlessly following the crowd. But scientists have discovered that the creatures are far more intelligent than they are given credit for.

Sheep have the brainpower to equal monkeys and, in some tests, even humans, researchers found.

They have advanced learning capabilities, are adaptable, can map out their surroundings mentally and may even be able to plan ahead.

Despite the strong arguments for vegetarianism and veganism, meat and dairy are expected to be the fastest-growing part of global food demand:

Rise of the carnivores

Moreover, an increasing proportion of the population is living in cities, and dollar for dollar city-dwellers eat more food and especially more processed foods than their country cousins. They also tend to be richer and able to afford pricier food, such as meat. So meat demand will rise strongly. In 2000, 56% of all the calories consumed in developing countries were provided by cereals and 20% by meat, dairy and vegetable oils. By 2050, the FAO thinks, the contribution of cereals will have dropped to 46% and that of meat, dairy and fats will have risen to 29%. To match that soaring demand, meat production will need to increase to 470m tonnes by 2050, almost double its current level. Output of soyabeans (most of which are fed to animals) will more than double, to 515m tonnes.

Overall, the FAO reckons, total demand for food will rise about 70% in the 44 years from 2006 to 2050, more than twice as much as demand for cereals. But that is still less than half as much as the rise in food production in the 44 years from 1962 to 2006. So according to the FAO’s Kostas Stamoulis, producing enough food to feed the world in the next four decades should be easier than in the previous four.

SIR – No solution to farming is viable unless we tackle the issue of consumption. In order to achieve a fairer balance in the world it would help if people in rich countries cut their meat and dairy consumption (which is also healthier). Crops should be used for feeding people, not for animal feed or biofuels. Research by the Potsdam Institute and the Alpen Adria University, in a study called “Eating the Planet”, proposes feeding the world by 2050 using humane and sustainable farming without a big change in land use, but only if meat consumption is moderated.

Joyce D’Silva

Compassion in World Farming

Godalming, Surrey

SIR – Producing animal protein is costly in terms of land and water use. A cow needs up to ten kilograms of feed to produce one kilogram of meat. A pig needs around five kilos and a chicken around three. The best part of the world’s maize and soyabean crops goes to feeding animals.

Separately, before poor farmers start buying seeds from big Western seed companies they should try some basic technologies such as crop rotation, green fertilisers and agroforestry. Those techniques, which are being implemented in many African countries, have the potential to increase yields and do much more to preserve the environment than planting large areas with one or two hybrid seeds.

Ernst Bertone Oehninger

Getulina, Brazil

SIR – Why not provide incentives for countries to curb excess consumption using phased-in tradable quotas? Countries failing to bring average consumption to below 3,000 calories a day could buy entitlements from grossly under-consuming countries, which could invest the proceeds in targeted grants aimed at eradicating the hunger that needlessly afflicts a billion people.

Andrew Macmillan

Scansano, Italy

Ignacio Trueba

Madrid

Q. Well, that’s certainly not what you’d expect from the media reaction to the paper. How did you reach that conclusion?

A. There is one particular type of resistance found by the researchers that is a big red flag for the influence of farm antibiotics, and that is resistance to the antibiotic tetracycline.

Let’s back up. When someone gets an infection, you give them a drug. Maybe it’s not the right dosage and the bacteria become more resistant to that drug. If the bacteria are never exposed to the drug, it’s unlikely they’ll become resistant.

Yet lots and lots of the bacteria that were analyzed in this study were resistant to tetracycline. And doctors haven’t historically given tetracycline to humans with MRSA infections. It’s not one of the major drugs. But animals get lots of tetracycline. The MRSA strain in livestock that was first identified back in 2004 that went from pigs to humans was tetracycline-resistant. In fact, that form of resistance was a big arrow pointing back to the drugs given to the pigs.

And indeed, when you look at all the bacteria samples that the Iowa team analyzed you see tetracycline resistance in lots of them. [Whereas] the human strains of MRSA found on the meat were probably put there by a slaughterhouse worker or a butcher or someone handling it in the supermarket.

These results turn this paper on its head. What it says is not, “Oh, farm antibiotics aren’t having that big an effect.” The prevalence of tetracycline resistance in all forms of MRSA tell us that farm antibiotics are a much bigger deal than anybody realized.

There’s little doubt in my mind that if those were dogs in distress in that truck instead of pigs, my actions would be applauded and it would be the driver facing charges instead. This double standard should have everyone questioning the ethics of the meat, dairy and egg industry, our legal system and our food choices. Like dogs, pigs are friendly, loyal and sensitive animals who have a strong sense of self and intelligence. They are playful and affectionate: they love to snuggle. They feel love and joy, but also pain and fear. They possess protective feelings for their families and friends. Pigs have been known to courageously jump into water to rescue drowning children.

NICK SMITH may be the first politician to be immortalised in horse manure. Before the recent general election, a super-sized sculpture depicting the environment minister, trousers down, squatting over a glass, was paraded through central Christchurch. It was carved from dung in protest at an alarming increase in water pollution. Data published in 2013 suggested that it was not safe for people to submerge themselves in 60% of New Zealand’s waterways. “We used to swim in these rivers,” says Sam Mahon, the artist. “Now they’ve turned to crap.”

…

New Zealand is a rainy place, but farmers are also criticised for causing rivers to shrivel and groundwater to fall in certain overburdened spots. One recent tally suggested that just 2,000 of the thirstiest dairies suck up as much water as 60m people would—equivalent to the population of London, New York, Tokyo, Los Angeles and Rio de Janeiro combined. Most is hosed on the stony Canterbury region, including the Mackenzie Basin. Earlier this year locals were forced to rescue fish and eels from puddles which formerly constituted the Selwyn river, after drought and over-exploitation caused long stretches to dry up.

…

Earlier this year the National Party launched a plan to make 90% of rivers “swimmable” by 2040. Yet it ignored several recommendations of a forum of scientists and agrarians established to thrash out water policy, and removed elected officials from an environmental council in Canterbury after they attempted to curb the spread of irrigation. One of its big initiatives to improve water quality involved lowering pollution standards, making rivers look much cleaner at a stroke.

…

Environmentalists argue that the national dairy herd should be cut to prevent further damage. That may not be as hard on farmers as it sounds, argues Jan Wright, a former parliamentary commissioner for the environment. She says recent growth in the industry has been relatively inefficient, denting margins. Yet the chances of change are slim. The regulations governing Fonterra, a big dairy co-operative, encourage volume more than value, says Kevin Hackwell of Forest & Bird, a pressure group. And pollutants moving through groundwater can take decades to emerge in lakes. The worst may still be to come.

Humans have had a profound impact on the prevalence of other species. Dr Bar-On’s research indicates that over the short span of human history on Earth (specifically after a large period of extinction that began 50,000 years ago) the biomass of wild mammals has decreased to a sixth of its previous value. Meanwhile, the carbon count of domesticated poultry grew to three times higher than that of every species of wild bird combined. Humans and their livestock have come to outweigh all other vertebrates on the planet with the exception of fish. That is not to say fish were spared. The biomass of fish is thought to have decreased by around 100m tonnes during humanity’s tenure. And the dominance of plants, although it is still overwhelming, was far greater before the start of human civilisation. Dr Bar-On suggests that the total biomass of plants has fallen to just half its previous level.

In rich countries people go vegan for January and pour oat milk over their breakfast cereal. In the world as a whole, the trend is the other way. In the decade to 2017 global meat consumption rose by an average of 1.9% a year and fresh dairy consumption by 2.1%—both about twice as fast as population growth. Almost four-fifths of all agricultural land is dedicated to feeding livestock, if you count not just pasture but also cropland used to grow animal feed. Humans have bred so many animals for food that Earth’s mammalian biomass is thought to have quadrupled since the stone age.

A report prepared for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change suggested that a move away from meat and towards plant-based diets could help fight global warming, but it pulled back from recommending that people become vegetarians. Companies selling plant-based products have seen their share prices soar this year.

At the moment, the market for meat substitutes is tiny. Euromonitor, a market-research firm, estimates that Americans spend $1.4bn a year on them, around 4% of what they spend on real meat. Europeans also chomp through about $1.5bn-worth of meatless meat a year, but this is 9-12% of what they spend on animal flesh.

…

Demand for plant-based meat is driven by a combination of environmental, ethical and health concerns. Raising animals for meat, eggs and milk is one of the most resource-intensive processes in agriculture. According to the un’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, it generates 14.5% of global greenhouse-gas emissions. Globally, demand for meat from animals is shooting up as people in developing countries grow richer and can afford to feast on flesh. In rich countries, by contrast, an increasing number of people say they would like to eat fewer animals. They may even mean it.

Berlin’s university canteens go almost meat-free as students prioritise climate | Germany | The Guardian

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/31/berlins-university-canteens-go-almost-meat-free-as-students-prioritise-climate

20 meat and dairy firms emit more greenhouse gas than Germany, Britain or France | Meat industry | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/sep/07/20-meat-and-dairy-firms-emit-more-greenhouse-gas-than-germany-britain-or-france

If turning aurochs into cattle, wolves into dogs or teosinte into maize sounds like a sideshow compared with transforming the composition of the atmosphere, looting the oceans or destroying the rainforests, consider a few facts. The most common species of bird is Gallus gallus, the domestic chicken. Even excluding people themselves, the biomass of domesticated mammals exceeds that of the wild sort by a factor of 14. A third of Earth’s dry land (deserts and ice caps included) is devoted either to growing domesticated plants for human consumption or to the nutrition of domestic animals.

https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/humans-have-altered-other-species-as-well-as-the-environment/21805519