Responding to an unusually poor article, written by Lorrie Goldstein and printed in the Toronto Sun, I wrote that: “If you want high human welfare and prosperity for decades and generations ahead, dealing with climate change is not optional. The longer Canada waits to begin the process of going carbon-neutral, the more costly and painful that process will be.”

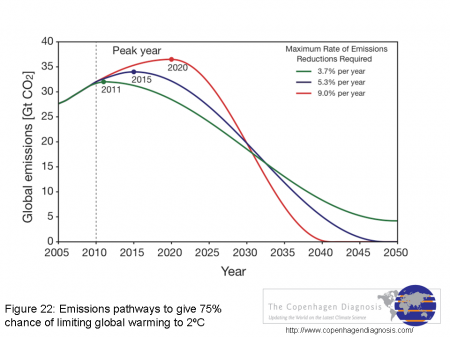

The above graphic, included in the recent Copenhagen Diagnosis, illustrates this situation nicely. The graphic shows three different pathways, each of which would give humanity a 75% chance of limiting warming to 2°C – a target that has been widely endorsed by governments, including those of the UK and EU. In a scenario where global emissions peak in 2011, they would only need to fall to about 5 gigatonnes by 2050, a reduction rate of 3.7% per year. Waiting just four more years, and having them peak in 2015, increases that to 5.3% per year. In the scenario with the 2015 peak, humanity as a whole needs to be carbon neutral before 2050, in order to provide the 75% certainty of avoiding more than 2°C of warming. Waiting until 2020 means that emissions need to fall by 9% per year afterwards, with carbon neutrality reached around 2040.

Bear in mind that these are global pathways. Under a contraction and convergence approach, where countries cut emissions while simultaneously becoming more equal in terms of per capita emissions, Canada would need to cut even faster. This illustrates firstly how wrongheaded it is to hope for a few more years of a hydrocarbon boom before we start the process of adjustment. It also illustrates the urgency of getting an effective global agreement in place soon. This isn’t an issue on which we can simply doddle for a decade. If we don’t want to see our children living in a transformed world, humanity needs to act fast and on a massive scale.

On a personal level, this may also bring some clarity to the many discussions we’ve had here about carbon ethics. If we individually want to mirror what the world as a whole needs to do, we should be planning to have our personal emissions peak virtually instantly, and fall every year thereafter. People who are my age should be thinking seriously about the possibility of living carbon-neutral lives by the time they face retirement – and about what accomplishing that would require.

A post in response:

“Taking into account the importance of the societal, my claim is that it is desirable that we “mirror what the world needs to do” – together. The emphasis needs to be on the “we”, not on the “as individuals”. Rather than acting “individually” – any action to be effective must foster social movements, activism, political pressure, and so on. I don’t think it is particularly virtuous to live a “moral” (pious), personally low carbon life – the relevant virtue here is in spurring and organizing the social transformation we so desperately need if we want our children not to live in a much more violent and hostile place than we. Of course, I do not mean to construct a false opposition between personal and social action. Rather, what I mean to show is that a personal action can either be individualizing or fostering of a social movement.”

If we individually want to mirror what the world as a whole needs to do, we should be planning to have our personal emissions peak virtually instantly, and fall every year thereafter.

As you said before, dealing with climate change is like changing the course of a huge cruise ship. What is important now is altering the overall direction, not changing the individual lifestyle choices of activists.

Besides, it is impossible for the world’s current six billion people to go carbon neutral without enormous changes in infrastructure.

Those curves are still sobering, however. It doesn’t seem like anyone has the will to start on the first part of the green curve – and it is hard to imagine what the middle of the red curve would be like.

“The problem is not a technological one. The human race has almost all the tools it needs to continue leading much the sort of life it has been enjoying without causing a net increase in greenhouse-gas concentrations in the atmosphere. Industrial and agricultural processes can be changed. Electricity can be produced by wind, sunlight, biomass or nuclear reactors, and cars can be powered by biofuels and electricity. Biofuel engines for aircraft still need some work before they are suitable for long-haul flights, but should be available soon.

…

It is all about politics. Climate change is the hardest political problem the world has ever had to deal with. It is a prisoner’s dilemma, a free-rider problem and the tragedy of the commons all rolled into one. At issue is the difficulty of allocating the cost of collective action and trusting other parties to bear their share of the burden. At a city, state and national level, institutions that can resolve such problems have been built up over the centuries. But climate change has been a worldwide worry for only a couple of decades. Mankind has no framework for it. The UN is a useful talking shop, but it does not get much done.

…

The problem will be solved only if the world economy moves from carbon-intensive to low-carbon—and, in the long term, to zero-carbon—products and processes. That requires businesses to change their investment patterns. And they will do so only if governments give them clear, consistent signals.”

“Until Copenhagen, the aim was to set targets for major emitters of greenhouse gases that would limit warming to 2 °C. That required, as a first step, that by 2020 industrialised countries cut emissions by 25 to 40 per cent compared with 1990 levels.

While that target remains an option in draft deals, most negotiators say they will have to accept whatever pledges industrialised countries are prepared to make. Right now those pledges add up to cuts of between 12 and 19 per cent, according to the UN climate secretariat. And there are loopholes that could mean even these pledges amount to virtually nothing.

“As things stand now, we will not be able to halt the increase in global greenhouse gas emissions in the next 10 years,” UN chief negotiator Yvo de Boer said in Bonn. “The 2-degree world is in danger. The door to a 1.5-degree world is rapidly closing.” De Boer is stepping down at the end of this month, and his successor, Costa Rican diplomat Christiana Figueres, said her priority was “rebuilding trust” rather than setting objectives.”

The IEA also looked at what it might take to hit a two-degree target; the answer, says the agency’s chief economist, Fatih Birol, is “too good to be believed”. Every signatory of the Copenhagen accord would have to hit the top of its range of commitments. That would provide a worldwide rate of decarbonisation (reduction in carbon emitted per unit of GDP) twice as large in the decade to come as in the one just past: 2.8% a year, not 1.4%. Mr Birol notes that the highest annual rate on record is 2.5%, in the wake of the first oil shock.

But for the two-degree scenario 2.8% is just the beginning; from 2020 to 2035 the rate of decarbonisation needs to double again, to 5.5%. Though they are unwilling to say it in public, the sheer improbability of such success has led many climate scientists, campaigners and policymakers to conclude that, in the words of Bob Watson, once the head of the IPCC and now the chief scientist at Britain’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, “Two degrees is a wishful dream.”

Climate pledges fall short, says UN

By Richard Black Environment correspondent, BBC News

The promises countries have made to control carbon emissions will see temperatures rise by up to 4C during this century, a UN report concludes.

The report, from the UN Environment Programme (Unep), comes days before the opening of this year’s climate summit.

It concludes there is a significant gap between what science says is necessary to constrain temperature rise and what governments have pledged to achieve.

But with extra political will, it says, warming could be kept much lower.

On Sunday, scientists released data showing that the recession curbed emissions from fossil-fuel burning by only 1.3% during 2009, and that they are set to begin rising again as the global economy cranks up once more.

Unep’s analysis shows that even if governments implement all they have pledged to do, that would “…imply a temperature increase of between 2.5-5C [from pre-industrial times] before the end of the century”.

Davis, S.J., K. Caldeira, and H.D. Matthews. 2010. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science 10 September, 2010 Vol 328 pp 1330-1333.

The long lifetime of existing transportation and energy infrastructure means that continued emissions of CO2 from these sources are likely for a number of decades. This ‘infrastructural inertia’ alone is projected to produce a warming commitment of 1.3°C above the pre-industrial era. This result emphasizes that extraordinary measures will be required to limit emissions from new energy and transportation sources if global temperature is to be stabilized below 2°C.

Climate modeling has demonstrated that even if atmospheric composition was fixed at current levels, continued warming of the climate would occur due to inertia in the climate system. This form of climate change commitment has become widely recognized. Davis et al. focus attention on inertia in human systems, by asking ‘what CO2 levels and global mean temperature would be attained if no additional CO2-emitting devices (e.g., power plants, motor vehicles) were built but all the existing CO2-emitting devices were allowed to live out their normal lifetimes?”. Barring widespread retrofitting or early decommissioning of existing infrastructure, these committed emissions represent ‘infrastructural inertia’. The authors developed scenarios of global CO2 emissions from existing infrastructure directly emitting CO2 to the atmosphere for the period 2010 to 2060 (with emissions approaching zero at the end of this time period) and used the University of Victoria Earth System Climate Model to project the resulting changes in atmospheric CO2 and global mean temperature. Projections with low, mid and high emissions scenarios led to projected global average warming of 1.3°C (1.1° to 1.4°C) above the pre-industrial era. Since new sources of CO2 are bound to be built in the future in order to satisfy growing demands for energy and transportation, the committed warming from existing infrastructure makes clear that satisfying these demands and achieving the 2°C target of the Copenhagen Accord will be an enormous challenge.

Summary courtesy of Environment Canada

World CO2 Emissions May Rise 43% by 2035 on Coal Use, OPEC Says

In engagements with young people in particular, I like to introduce the notion that, “We are the U-turn Generation.” The concept is this: all of us who have the courage to look the science of global warming full-on wrestle with despair. A clear understanding of what the scientific studies are telling us is that wealthy industrialized societies must be carbon-zero by 2050. Even then, we will still face the challenge of pulling accumulated GHGs out of the atmosphere, in order to get global CO2 parts per million (PPM) down to 350, if devastating ecological and social upheaval and harm is to be avoided. We are forced to live with the uncertainty of whether this Herculean global task can be accomplished. But for now, the task of this generation is the U-turn – to change the direction of the path we are on – to see global emissions slow, and over the next 30-40 years, drop to zero.

Under the Paris deal, each country put forward a proposal to curtail its greenhouse-gas emissions between now and 2030. But no major industrialized country is currently on track to fulfill its pledge, according to new data from the Climate Action Tracker. Not the European Union. Not Canada. Not Japan. And not the United States, which under President Trump is still planning to leave the Paris agreement by 2020.

Fossil fuel emissions to reach an all-time high in 2017, scientists say, dashing hopes of progress

Emissions are forecast to reach around 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning and industrial activity in 2017

The World’s Astonishing Dependence On Fossil Fuels Hasn’t Changed In 40 Years

—

The world’s astonishing dependence on fossil fuels hasn’t changed in 40 years

This year’s “Emissions Gap” report from the UN, published in October, shows that the first set of climate pledges submitted by 164 countries corresponds to barely a third of the cut in emissions needed to keep warming below 2°C (see chart). Studies suggest that these “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) would probably result in temperatures 2.9-3.4°C higher than in pre-industrial times—and that only if they are fully implemented, which seems unlikely.

Electricity also rewards co-operation. Because renewables are intermittent, regional grids are needed to ship electricity from where it is plentiful to where it is not. This could replicate the pipeline politics that Russia engages in with its natural-gas shipments to Europe. More likely, as grids are interconnected so as to diversify supply, more interdependent countries will conclude that manipulating the market is self-defeating. After all, unlike gas, you cannot keep electricity in the ground.

An electric world is therefore desirable. But getting there will be hard, for two reasons. First, as rents dry up, authoritarian oil-dependent governments could collapse. Few will miss them, but their passing could cause social unrest and strife. Oil producers had a taste of what is to come when the price plunged in 2014-16, which led to deep, and unpopular, austerity measures. Saudi Arabia and Russia have temporarily stopped the rot by curtailing production and pushing oil prices higher, as part of an “OPEC+” agreement. They need high prices to buy time to wean their economies off oil. But the higher the oil price, the greater the incentive for energy-thirsty behemoths like China and India to invest in renewable-powered electrification to give themselves cheaper and more secure supplies. Should the producers’ alliance crumble in the face of a long-term decline in demand for oil, prices could once again tumble, this time for good.

That will lead to the second danger: the fallout for investors in oil assets. America’s frackers need only look at the country’s woebegone coalminers to catch a glimpse of their fate in a distant post-oil future. The International Energy Agency, a forecaster, reckons that, if action to limit global warming to below 2°C accelerates in coming years, $1trn of oil assets could be stranded, ie, rendered obsolete. If the transition is unexpectedly sudden, stockmarkets will be dangerously exposed.

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2018/03/15/welcome-an-electric-world.-worry-about-the-transition

Global energy-related carbon-dioxide emissions grew by 1.4% last year, according to the International Energy Agency, to a record 32.5 gigatonnes. Some big economies, such as America and Japan, saw their emissions decrease; Britain’s fell by 3.8%. Asian countries accounted for two-thirds of the global increase. Despite the growth in renewables, the share of fossil fuels in the world’s energy mix remains at 81%, the same level it has been for three decades.

The authoritative new report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sets the world a clear target: we must reduce emissions of greenhouse gases to net zero by the middle of this century to have a reasonable chance of limiting global warming to 1.5C.

…

Human activities are currently emitting about 42bn tonnes of carbon dioxide every year, and at that rate the carbon budget – allowing us a 50-50 chance of keeping warming to 1.5C – would be exhausted within 20 years.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/oct/08/we-must-reduce-greenhouse-gas-emissions-to-net-zero-or-face-more-floods

Net zero emissions are the end goal, because that is the ONLY way to stabilize atmospheric concentrations as per the original UNFCCC (1992). How fast we reach net zero determines how much warming we see.

But perhaps the most dangerous misconception about the climate crisis is that we have to “lower” our emissions. Because that is far from enough. Our emissions have to stop if we are to stay below 1.5-2C of warming. The “lowering of emissions” is of course necessary but it is only the beginning of a fast process that must lead to a stop within a couple of decades, or less. And by “stop” I mean net zero – and then quickly on to negative figures. That rules out most of today’s politics.

The fact that we are speaking of “lowering” instead of “stopping” emissions is perhaps the greatest force behind the continuing business as usual. The UK’s active current support of new exploitation of fossil fuels – for example, the UK shale gas fracking industry, the expansion of its North Sea oil and gas fields, the expansion of airports as well as the planning permission for a brand new coal mine – is beyond absurd.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/23/greta-thunberg-full-speech-to-mps-you-did-not-act-in-time

Time difference between my original post and this Greta Thunberg tweet:

9 years 5 months 29 days

495 weeks 2 days

3467 days

9.49 years

Energy-related carbon emissions grew by 1.7% in 2018 to a historic high of 33bn tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency. That was in part because of adverse weather, which increased demand for heating and cooling. China’s emissions were up by 2.5%, and America’s by 3.1%. Emissions declined in Britain, France, Germany and Japan. See article.

“In the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] SR-1.5 reports that came out last year, it says on page 108 in chapter 2 that to have a 67 per cent chance of staying below 1.5 degrees of global temperature rise — the best odds given by the IPCC — the world had 420 gigatonnes of CO2 left to emit back on Jan. 1, 2018.

And today, that figure is already down to less than 350 gigatonnes.”

Greta Thunberg, in her own words, at the Montreal climate march

Carbon Dioxide Emissions To Rise Through 2040

Last week the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its World Energy Outlook (WEO) 2019. The WEO projects global energy supply and demand through 2040

In bleak report, U.N. says drastic action is only way to avoid worst effects of climate change

The report warns that global temperatures are on pace to rise as much as 3.9 degrees Celsius (7 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century.

Analysis: Emissions spiked under Trump and the world is taking notice

At a summit in Paris in 2015, 188 countries pledged to curb their greenhouse-gas emissions. Collectively, these pledges, known as “nationally determined contributions” or NDCs, fall well short of what is needed to achieve another part of the Paris agreement, which is to avoid more than 2°C of warming above pre-industrial temperature levels. A report by the United Nations Environment Programme finds, however, that even these unambitious targets will probably be missed. Researchers studied policy documents from big fossil-fuel-producing countries to calculate how much coal, oil and natural gas is likely to be extracted over the next 20 years. According to these documents, global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels will reach 41 gigatonnes by 2040. That is higher than the 36 gigatonnes implied by the NDCs—and well above the 19 gigatonnes needed to keep warming below 2°C.

Turning out the light: criteria for determining the sequencing of countries phasing out oil extraction and the just transition implications

There is a pressing need to curb the extraction of fossil fuels, alongside their use and consumption, to remain within reach of the 1.5C global warming limit. Yet, a reduction in the supply of fossil fuels does not inherently indicate a just or equitable transition. A growing number of papers are proposing approaches and criteria for determining the allocation of remaining production of fossil fuels and the sequencing of countries phasing out extraction and production. With a focus on oil, this paper identifies, and reviews 15 criteria found in the literature for determining the sequencing of phase out of fossil fuel supply. These criteria are economic efficiency, wealth, dependence, development, historical responsibility, procedural justice, and variations within these approaches. In addition, this paper reviews the extent to which these criteria have been operationalized and discusses the just transition implications of pursuing a fossil fuel supply phase out based on the criteria and indicators identified. This review suggests that the sequencing of countries that phase out oil extraction differs depending on the criteria adopted but that there are gaps in the criteria identified and in their operationalization, with implications for how to usher in just transitions. This paper calls for a more holistic view of the equity implications of a global phase out, supported by further research broadening and deepening the scope of equity considerations.

Key policy insights:

Without policy interventions, market dynamics alone are unlikely to lead to a deliberately equitable distribution of the remaining extraction of oil in line with a 1.5C global warming goal.

The sequencing of countries phasing out oil extraction differs depending on the criteria adopted and sequencing based on individual criteria can lead to ill-considered outcomes.

There is a gap in the criteria and indicators needed to determine a sequencing of a global phase out that is aligned with a just transition, which hampers informed decision-making and a holistic assessment of circumstances across countries.

Basing a phase out on an incomplete assessment of indicators poses a risk to just transition, particularly regarding development needs and procedural justice.

Global greenhouse gas emissions at all-time high, study finds

Scientists say world is burning through ‘carbon budget’ that can be emitted while staying below 1.5C

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jun/08/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-at-all-time-high-study-finds

EU must cut carbon emissions three times quicker to meet targets, report says | Greenhouse gas emissions | The Guardian

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/oct/24/eu-must-cut-emissions-three-times-more-quickly-report-says

Climate crisis: carbon emissions budget is now tiny, scientists say

Having good chance of limiting global heating to 1.5C is gone, sending ‘dire’ message about the adequacy of climate action

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/oct/30/climate-crisis-carbon-emissions-budget